On a recent Tuesday morning in Boston, I took the Green Line to the office of Kevin Outterson. Small and academic, with a view across the Charles River into Cambridge, the space is unassuming. Yet, it is technically the headquarters of the largest public-private partnership dedicated to fighting antibiotic resistance in the world.

Outterson is the executive director of the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator, more explicitly known as CARB-X. Run out of Boston University, CARB-X is a fund that provides grants, usually a couple million dollars at a time, and support to companies working on marketable, but scientifically sound, measures to replace the antibiotics that are beginning to lose their battle against ever-evolving bacteria after decades of dominance.

“Antibiotics make up the most important drug class in human history,” Outterson said. “And it self-destructs through bacterial evolution. Globally, we’re still interacting with bacterial evolution in a harmful way through use, overuse, and inappropriate use. We’re messing with something dangerous here: pathogenic bacterial evolution. The only way we can avoid falling back into a pre-antibiotic era is to continue to innovate.”

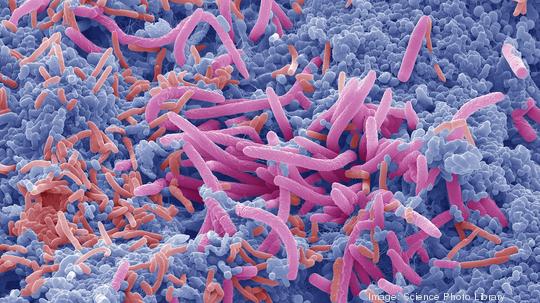

It’s difficult to overstate how devastating a return to the pre-antibiotic era would be. Imagine falling outside and scraping your knee. Even now, that scrape could get infected with staphylococcus, an extremely common bacteria. But if Neosporin failed, you’d be left in the lurch. Now think about our basic health infrastructure. Common procedures like knee replacements would be impossible, because hospitals wouldn’t be able to sanitize against lethal pathogens. Heart surgery would be a distant dream. Even now, hospital-acquired infections lead to some 98,000 deaths in the U.S. annually.

Outterson, who also co-directs the renowned Health Law Program at Boston University, describes antibiotic development as an ever-running treadmill. If diseases are being mitigated early on through vaccinations and hygienes, and if antibiotics are being prescribed and used conservatively—lessening the potential for resistance—the treadmill moves slowly. Drug developers can keep up.

“But if there's sewage running on the streets, and people overusing antibiotics, and antibiotics being dumped into the water supply—which was true for decades in India—then the treadmill goes faster,” Outterson said. “The faster it goes, the more urgent the need for new antibiotics.”

As it stands, the urgency is increasing. Each year in the U.S., at least 2 million people get an antibiotic-resistant infection, and at least 23,000 people die, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Worldwide, the death toll is estimated at 700,000 people a year. Because resistance is developing faster than new drugs are being developed, the death toll is expected to rise to 10 million per year and cost the world as much as $100 trillion in lost economic activity by 2050.

CARB-X was launched in 2016 as a stopgap measure, a massive fund dedicated to accelerating drug development, including new classes of antibiotics and other novel therapies. It’s a public-private partnership, funded by the US Department of Health and Human Services Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), along with the National Institutes of Health and several international governments and charities.

Initially, CARB-X grew out of an initiative spearheaded by the Obama White House: the U.S. National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. As a placeholder, the National Strategy included plans for a “biopharmaceutical accelerator;” a year later, BARDA put out a request for grant proposals to fulfill that mission. A consortium that Outterson put together—the beginnings of CARB-X—was awarded the grant.

Its task since then has not been small. CARB-X has given more than $100 million to small pharmaceutical companies since it was launched in 2016, funding private projects like new antibiotic classes, vaccines, and microbiome treatments. Ultimately, it will give out up to $550 million by 2021, with plans to grow beyond that. Outterson said CARB-X is currently making plans for years six through 10.

“We're not just looking for an interesting lab to continue. We're looking for a product that can move towards approval,” Outterson said. “Our goal is to push into Phase II clinical trials and get approval for as many first-in-class, amazingly novel antibacterial alternatives [as possible]. … Our strategy is to intervene and to improve the quality of the clinical pipeline, and to do so by making thoughtful, science-based investments around the world.”

Between securing funding, dealing with the red tape that typically comes with academic or government-funded research, and the clinical trial process itself, new drug development can take 10 to 15 years. (For new drugs to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration, they must progress through three phases of clinical trials. The third phase can include potentially thousands of patients.) CARB-X aims to expedite that process.

“If we weren't doing it, there'd be 50 of these companies that would be bankrupt. All these projects would be stopped.”

So far, it’s working. Forge Therapeutics, a biotech startup in San Diego, has twice received CARB-X funding, most recently in February to develop an antibiotic to treat serious lung infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria, including multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. CEO Zak Zimmerman said the support has been absolutely vital—not just the funding, which Forge rolled into its multimillion-dollar Series A funding, but also access to leaders in the antibiotic space who are affiliated with CARB-X.

“We wouldn't be as far along as we are,” Zimmerman said. “We’ve moved from discovery, looking at a target, identifying some hits, and going into the optimization, and now we have development candidates that are moving forward, ready for IND-enabling studies. We've been able to do that over the last two years, which is very fast for the industry.”

Zimmerman estimates the approval process for CARB-X funding took about half the time as securing funding from the NIH or other traditional institutions.

The importance of this speed is not lost on Outterson.

“If we weren't doing it, there'd be 50 of these companies that would be bankrupt,” Outterson said. “All these projects would be stopped.”

Still, CARB-X is not a cure-all. In April, antibiotics development company Achaogen announced it had filed for bankruptcy. The company had actually received $2.4 million from CARB-X just a year prior. (Achaogen representatives were not available for comment, a spokeswoman said.) In a column for WIRED, journalist Maryn McKenna, who writes almost exclusively about antibiotic resistance, rightfully blamed the market. “The larger story of the Achaogen bankruptcy is that the financial structures that sustained antibiotic development for decades are broken,” McKenna wrote. “If we want new antibiotics, we’re going to have to find new ways to pay for them.”

Currently, CARB-X is one of the world’s largest providers of so-called push incentives, the model through which it gives money to early-stage drug development. Ultimately, push incentives may not be the way forward. Some experts are now advocating for pull incentives, essentially the reverse: Funds would give pharma companies cash for a job well done if they successfully get their drugs developed and on the market.

Outterson is not against pull incentives. In fact, he thinks it would be a good thing if they gained traction; it would allow CARB-X to dial it back a bit. The fund was always meant to be a temporary measure, after all.

“If the U.S. and Europe enacted a sufficiently robust pull incentive, the need for CARB-X would go down dramatically,” Outterson said. “If there were a $2 or $3 billion carrot hanging out there for biotech investors, then private capital would go chasing all the great projects we’re funding now. Instead of starving for money, they would have multiple suitors looking to fund their projects. We're here as a stopgap.”

Until then, though, CARB-X remains an invaluable resource for the scientists on the front lines of novel antibacterial drug development. Unable to woo private equity, companies like Forge Therapeutics turn instead to CARB-X to pursue their noble dreams.

“It’s hard to get VC money for antibiotics,” Zimmerman said pointedly. “CARB-X has filled this void. They provide critical investment into this space.”

Editor's note: Read our profile on Selux Diagnostics, a startup working on personalized antibiotic treatments.