It’s a common story that you might not believe is true until it happens to you: A call to a childcare center in Wake County where a mom-to-be is told there’s a two year wait list for infants.

It’s an infuriating reality for working moms in the Triangle region, where growth keeps happening and childcare services can’t keep up with the demand.

But for some savvy entrepreneurs, it’s also an opportunity, one that those who follow labor statistics say isn’t going away despite some relief since the pandemic began in 2020.

Tom Barkin, CEO of the Richmond Fed, said there was widespread labor force worry when, after Covid, “it really hit participation by women quite hard.”

Childcare centers and schools shut down, forcing some women to quit their jobs.

Barkin said that nationally, it’s bounced back.

“Women’s labor force participation accelerated,” he said, noting that it’s “higher than it was pre-Covid.”

Labor force participation for women ages 25 to 54 hit a high of 77.8 percent in June, dipping slightly to 77.4 percent in November. Barkin attributes some of the labor force comeback to hybrid work, “a more significant piece of the puzzle today than it was four years ago.”

“That gives a belief that balancing work and home might be more doable for a bigger part of the population,” he said, noting that much of the bounce back is coming from women with college degrees.

But childcare is still a major challenge, as burnout is causing many daycare workers to leave their jobs in search of higher paying careers, causing existing care centers to tighten.

As moms will tell you, balancing it all is still the wild, wild west, nearly four years after the pandemic began.

Inno spoke with two entrepreneurs who see opportunity in curbing the chaos.

My Girl Friday

A nanny by trade, Margaret Macfarlane launched household staffing firm My Girl Friday in 2011, initially to provide a network that could offer backup childcare.

CEOs, surgeons, founders: They couldn’t take a day off just because their nanny was sick. So My Girl Friday swooped in, connecting them to childcare workers as well as backup care, quickly averaging about 10 positions listed at any one time.

Then came 2020 and the client list went to zero in March. Gradually, a few listings popped back up, primarily from medical workers who didn’t have a work-from-home option. Then June hit and, all of a sudden, those one or two listings from medical households a week swelled to 30, and then 45.

“It was the most intense period of growth in my whole professional life,” she said.

People had realized remote work wasn’t going away, and they started to understand the complexities of trying to work at fast-paced companies while also managing toddlers.

The business took off, and it hasn’t really slowed down.

Macfarlane is taking advantage of the opportunity, having assembled a network of hundreds of nannies. Her firm, which has six full-time employees, takes a placement fee from families utilizing the service. After it connects a nanny to a family, it will provide backup care for the life of that contract.

The company is primarily bootstrapped, though it has had the support of Red Hatter and local investor Jeremy Zhang.

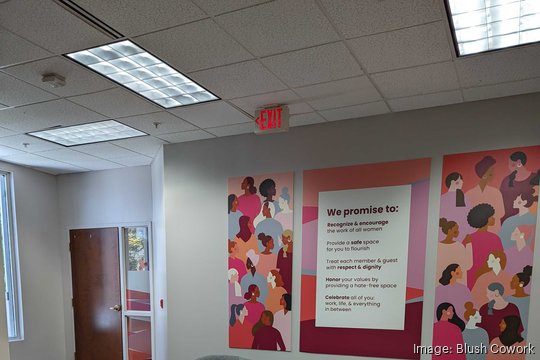

Gallery: Inside Blush Cowork in Cary

A peek inside Blush Cowork in Cary

Blush Cowork

Alison Rogers, founder of Blush Cowork in Cary, felt the childcare gap personally in 2020. She was working remotely “and really not doing a great job covering my employee duties and my parenting duties." That’s because her 3-year-old’s daycare was closed and her second grader was in remote learning.

“My employers were absolutely not understanding of the situation, and it was just really hard,” she said.

Rogers ended up being laid off – “not the most fun catalyst,” she said. But it was the kick she needed to start a women-focused coworking space with built in childcare. Today, she has 66 members, not including those who come in occasionally without a full membership.

Rogers bootstrapped the company, initially thinking she’d attract remote workers like her. The space turned into a place that primarily attracted entrepreneurs and women business owners, she said. And last month it was profitable.

Rogers is considering taking on additional capital, but is finding it difficult to connect with investors, as she’s in sort of a new category. But the need isn’t going away, she said.