On paper, Aisha Dozie would seem to be a entrepreneur Silicon Valley investors would be fighting to back.

She has an MBA from Harvard Business School and completed a professional career fellowship at Stanford University. She's lived overseas and worked for blue-chip Wall Street firms, including Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley.

She's also a repeat founder; her latest company, Bossy Cosmetics Inc. is her second startup. Bossy's revenues grew by 10 times last year and have already doubled that total in the year to date. On top of all that, Bossy's products are so well regarded that Oprah Winfrey placed the startup's Power Woman Essentials lipsticks on her "favorite things" list last year, and they'll be sold in JCPenney stores later this year.

And yet, since founding Palo Alto-based Bossy in 2018, Dozie struggled for years to raise venture funding for it. Rather than capital, the investors she met with gave her excuses or unsolicited advice to change Bossy's direction.

Why did Dozie have such a hard time finding funding? She chalks it up largely to one simple fact — the color of her skin. Dozie is Black.

"I literally feel like I don't matter," Dozie, Bossy's CEO, told the Business Journal. "Investors in Silicon Valley, the layers that I had to peel through — I just have stopped even trying."

Dozie's not some kind of conspiracy theorist, and she's definitely not alone in feeling that Silicon Valley devalues Black people. While the region has long been a mecca for entrepreneurs from around the nation and world, there's always been at least one big exception to that rule: It's never been a particularly welcoming place for Black founders.

Silicon Valley has few Black people

There are numerous reasons why Silicon Valley is not a bastion of Black tech entrepreneurship, according to founders, investors and others around the startup and venture industries. Due to historical and other reasons, the area has a small Black population and has done little to attract more Black people. The region's tech companies have done a poor job of recruiting and retaining Black tech workers or managers, the kinds of people who frequently go on to found tech startups. And the venture industry, which has few Black partners, has devoted very little of its capital — typically around just 1%, according to Crunchbase — to Black-led startups.

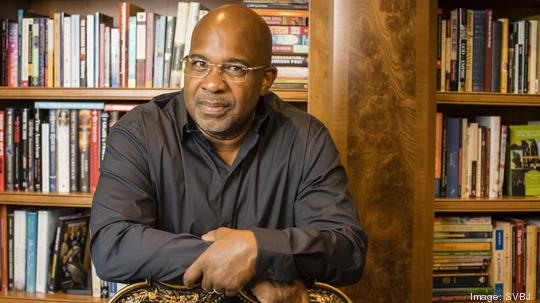

Silicon Valley is characterized by a lot of "sameness," said Matt Carter, the CEO of enterprise telecom startup Aryaka Networks Inc.

Carter, as a Black man, knows from experience. Prior to being hired by San Mateo-based Aryaka in 2018, he had been working in business for 30 years, including serving as CEO of publicly held Inteliquent Inc. and as a top executive at Sprint Corp. Despite that track record, when he interviewed for positions with Silicon Valley companies, he was repeatedly passed over, he said.

"Often they will look at you and say 'Here's what's wrong with you,' versus 'Here's what's right with you.' You get pigeon-holed," Carter said. He continued: "The Valley in general has paid a lot of lip service toward diversity and inclusion, and they need to be called out on it."

Perhaps the biggest challenge to Black tech entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley is the low population of Black people in the region. Just 2.9% of Santa Clara County's population is Black, and just 2.8% of San Mateo County's is, according to U.S. Census data. Black people comprise only slightly higher percentages in Fremont and Milpitas.

That's no accident. Restrictive covenants, redlining and other forms of housing discrimination excluded Black people from vast swaths of the Peninsula and the South Bay for much of the last century. More recently, gentrification and spiking housing prices have pushed out many residents, including Black people.

East Palo Alto, for example, was once a majority-Black area. As recently as 1980, 61% of its population was Black, according to U.S. Census data. Today, just 12% is.

"Most of the family and friends that (used to live in East Palo Alto), they have moved out to Hayward and Stockton and Tracy and all these places that are more affordable," said Tre Kirkman, a Black founder who based his startup in the Peninsula city because of his historical family ties there.

The tech giants employ few Black managers and engineers

The tech companies that dominate employment in Silicon Valley have done little to reverse that trend or past injustices. Historically, such companies have hired and retained few Black people, particularly for tech or managerial roles. Despite years of browbeating by activists and public acknowledgement by their own leaders of the importance of diversity, many such companies still employ relatively few Black professionals.

As of last year, for example, just 5.5% of Apple's U.S. tech workforce was Black and just 4% of those in its leadership ranks, according to its own diversity report. Meanwhile, only 5.3% of Google's overall U.S. workforce was Black, according to its diversity report.

The tech industry has had huge success convincing people from Asia and other areas to move to Silicon Valley and feel at home here, said Lisa Lambert, the founder and president of National Grid Partners. By contrast, the tech and venture industries have done a poor job of attracting Black tech professionals to the area, said Lambert, one of the few prominent Black investors in Silicon Valley.

"You can be proactive about bringing large communities from underrepresented groups into the Bay Area," said Lambert, whose Los Gatos-based outfit is the venture arm of National Grid PLC, an electricity and gas utility company headquartered in London. "We know how to do it here, and we haven't done it (for Black people). That makes me think that we don't want to."

That lack of effort has big follow-on consequences. Many Silicon Valley startups are founded by people who got their start as engineers or managers at the region's big tech firms.

But at least in the San Jose region, that pipeline of Black talent is barely flowing, because there are so few Black tech workers here.

Working at various times in Mountain View, Palo Alto and Menlo Park for companies including the then-Facebook Inc. and Palantir Technologies Inc., Deon Nicholas saw the problem up close.

"At times I'd be the only Black person on the engineering team," he said.

Few venture investors are Black

And there are further consequences of Silicon Valley's failure to attract and retain Black talent. Many startup founders go on to become mentors to the next generation of entrepreneurs, and a large proportion of venture capitalists got their start as founders.

But with so few Black founders having gone through the pipeline, there's a dearth of Black funders. As of 2020, just 4% of all those in venture industry that were involved in investment decisions were Black, according to a study from the National Venture Capital Association and Deloitte. Only 3% of venture partners were Black.

That matters, because of a phenomenon called pattern-matching that tends to dominate the venture industry. Investors tend to back founders who remind them of themselves or of other successful founders they've previously invested in. If the investors themselves aren't Black, and if the vast majority of the founders they've previously supported aren't Black, there's a good chance that they aren't going to see a new Black founder as a surefire bet.

Nicholas found that out as he was pitching his startup, Forethought Technologies Inc., to Silicon Valley funders. Even though Nicholas had a been an engineer in Silicon Valley for several years and had a stellar pedigree, investors seldom seemed to take him seriously upon meeting him. He quickly learned that he had to lead his pitches with his technical background to establish his credibility.

"If I started by just talking about my idea, you get this sense that they're just turning their head, like 'Who are you again?’" Nicholas said.

Julia Collins, who co-founded Zume Pizza, had similar experiences with the way Silicon Valley investors tend to discount Black entrepreneurs. When she was running Zume, prospective investors who visited its Mountain View office would often mistake her — a Black woman with years of experience founding and running food-related companies — for an administrative assistant.

"I would open the door, and they would either walk right past me, or they would say, 'Is the founder there?'" Collins said. "And that happened many times, not just once."

As Dozie was trying to raise funding for Bossy, investors — particularly male ones — tried to push her into serving a niche focused on Black and brown women rather than accepting that her startup could serve women of all races, ethnicities and skin colors, she said. One female investor rejected Dozie's pitch by saying she didn't invest in non-tech, "soft-type" companies, she said.

"I've heard it all," Dozie said.

There's a dearth of Black culture

For her part, Lambert tried to shake up Silicon Valley's status quo when it comes to supporting Black founders. Prior to joining National Grid, she worked for Intel Capital. The CEO at the time, Brian Krzanich, made a pledge to the Rev. Jesse Jackson to take concrete steps to promote diversity within the chip giant. Among those steps was a $125 million venture fund specifically dedicated to investing in startups founded by women and members of underrepresented minority groups.

Despite the high-profile move, few other tech companies or venture firms followed in Intel's footsteps.

"I thought there would be a series of other corporations like Intel doing the same thing ... I assumed that they would set up even a nominal fund," she said.

The small size of Silicon Valley's Black population — whether in the tech industry or not — has become its own obstacle for attracting and keeping Black tech workers and entrepreneurs here. Outside of East Palo Alto, there's relatively little in the way of Black culture in the South Bay or on the Peninsula.

The qualities of a place that matter most can amount to "just little things, like access to African-American food," said Robert Pinkerton, who co-founded Vori Inc. with Kirkman. "A good barber — you're going to have to go up to Oakland."

Vori is an exception to the larger trend about Black-founded startups. Pinkerton, Kirkman and Brandon Hill, who all met at Stanford, decided to base the company in East Palo Alto, because that's where Kirkman's family was from. Vori's headquarters is just a block away from his great aunt's house.

But even Kirkman understands how Silicon Valley can be a tough sell for other Black entrepreneurs.

"What is it about (Silicon Valley) that's drawing you in as an entrepreneur of color?" Kirkman said, suggesting that the answer is anything but obvious. "I feel at home here because I grew up here, but other times I feel othered."

Silicon Valley may have an even more difficult time attracting and developing Black founders going forward. In recent years — even before the Covid-19 pandemic — the region's big tech companies have been setting up major offices in other regions of the country, including some that are well-established centers of Black entrepreneurship. Venture investors have started to follow in their footsteps, spreading their investments far and wide from Silicon Valley.

The pandemic, which spurred a huge uptick remote work and forced companies to recognize that talented tech workers can live or be found in lots of other regions than the Bay Area, gave a boost to those trends. As a result, Black entrepreneurs may well have a better chance of raising venture funds by just staying where they are.

"Now we don't even have to fly, we can get on a phone call ... (and) find the next great person of color coming out of Miami, find the next great person of color coming out of Atlanta," said Tosh Ernest, head of SVB's Access to Innovation program, which is designed to help Black founders and investors across the country get access to funding. "We are running out of excuses in talking about the pipeline problem."

It's on investors to change the status quo

Much of the onus for addressing the lack of Black founders in Silicon Valley lies with venture investors, said Nicholas Brathwaite, a founding managing partner at Celesta Capital. They need to recognize that Black founders, even those who come from non-traditional backgrounds, can still build valuable businesses, he said. They also need to be patient with and help mentor Black founders and other entrepreneurs from underrepresented groups, he said.

"Many (Black founders) haven't been senior executives, because they haven't had the opportunity to be senior executives," Brathwaite said. "Many of them don't have the best pitch, but when you listen to them and dig deeper, you start realizing that these people are really smart, and they really understand this area very, very well and we can bring people to complement their skills."

If they don't start taking such steps, investors risk missing out on what could be outstanding companies.

Silicon Valley funders often invest in companies that are little more than big ideas. Despite being much more than an idea and growing just as fast as much more favored startups, Bossy couldn't interest them.

When Dozie did finally raise a $1 million round for her company earlier this year, the money didn't come from any of the big Menlo Park or San Francisco firms. Instead, she raised it from a collection of family, friends and angel investors.

“I'm a dark-skinned Black woman; that's not going to change," she said. "So if this is all you're going to see when you see me, there's nothing I can do about that."