From lasers and genetic research to precision instruments and 3D printing, regular transfers of hot new technologies from Lawrence Livermore National Lab to Tri-Valley companies have strengthened the regional economy for decades.

LLNL employs 3,179 Tri-Valley residents and made $43 million in procurements in fiscal year 2021 from area companies. In addition, the lab has active commercial licenses with nine companies in the Tri-Valley.

A key cultivator of this flourishing technology/business ecosystem is Rich Rankin, LLNL’s director of the Innovation and Partnerships Office. Rankin was already a successful inventor and businessman as well as former head of the tech transfer office at Idaho National Laboratory when he came out of retirement to join LLNL in 2013. The lab licenses 20 to 100 new developments and discoveries a year, Rankin said. The Business Times spoke with Rankin about the many mutual benefits of tech transfer between LLNL and the Tri-Valley.

Let’s start with the basics: What is your definition of tech transfer? It can mean different things to different people. Tech transfer to me is taking an invention of technology — software, technical creations and products — from the laboratory or the point of creation and moving them to a point where they have commercial benefit. I don’t necessarily mean it’s for sale, but it has a widespread benefit to the economy.

For example, at Livermore, we created technology associated with genomic detection that was turned into a product. The product was then turned into sales where there are a number of instruments around the world that one can take the human genome or other genetic materials, analyze it and come out with an identity signature.

In a case where it may not be for sale, we might provide additional capability, insight or knowledge that helps the government or commercial companies or universities gain knowledge. If you’re in the business of changing the world, sometimes that’s not something that rings up on a cash register.

How do you know when a technology is ready for commercialization? Technology transfer is an intersection of science and technology with business and law, maybe with a little political oversight. And in every discipline, every part of that cries to be the most important. We look at both the current market — if there’d even be one — and then we look at what we believe might emerge as a market or a need some time out, three to five years or sometimes more.

And then if there’s a need, is it likely that the environment that’s necessary to support that need will come to be? Will there be the right talent around? Will there be enough interested, engaged funding? Who are their users or their customers? The hardest part is picking the winner. We have quite a cadre of people who are in business or CEOs or serial entrepreneurs or what we call lab graduates — people that have taken technologies and made them successful — and people from other laboratories. In the end, though, it’s the market that makes that decision.

What are some of the challenges and risks inherent with tech transfer? To get big wins, you have to accept some risk — and I use that as an industry term, not that it’s hazardous or anything. We could invest three years of our time and effort in a new startup company, and then we get to the end of three years and we find out it doesn’t work, or that the market has changed or that Company X has come out with something that does it better or cheaper or faster. Or that the regulations change. That’s the case for any company bringing a product to market.

How do you keep up with the constant pace of innovation so that those surprises are as few as possible? Innovation occurs all over the place and is not restricted to labs or universities or companies. We look at patents being filed. We look at publications. We have lots of interactions with colleagues around the globe.

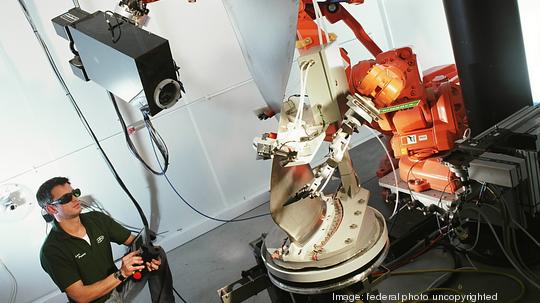

Can you offer a few examples of local tech transfers, either with existing Tri-Valley companies or creating new companies? Some of these companies are created around the technology that we have, and others are companies that we license to and that makes them successful in the marketplace. Some time ago there was a corporate challenge [from aircraft company Curtiss-Wright Corp.] to apply lasers to peening operations. You may remember that your dad or your grandfather had a ball-peen hammer and when you were doing something with metal, you’d essentially bang on it. That helps the metal be stronger. It helps it be more flexible. It helps it to last longer. There are other technologies designed to help do that.

So anyway, this challenge came along: How do I make my aircraft turbine blades better? And how do I make them safer? How do I make them last longer? How do I reduce my maintenance cost? Our guys at the lab applied lasers as essentially a giant hammer to treat the metal. And the treated blades in engine turbines last tenfold. So that means they’re that much safer and fail that much less often. That company has treated more than 100,000 jet engine fan blades and more than 500 discs.

Can you give an example of a new Tri-Valley company created by LLNL technology? Some time ago, some people left the lab to start a company called QuantaLife Inc. They took an instrument technology and developed it into something called a digital PCR (polymerase chain reaction) system. It’s genomics analysis. That company was successful, was sold largely to another company and the founders have cash in their pockets. So what do they do? They form other companies, and there have been several of those, and the grandchildren and beyond include 10x Genomics Inc. in Pleasanton, which is growing like a weed.

What kind of support does the lab offer as these companies grow? Is it just giving them a bit of a push out of the nest and letting them find their way? The lab has largely pushed them out the door. However, we do maintain good relationships. If you create a company out of whole cloth, you do not have the infrastructure the laboratory has. So being able to partner to do that, particularly laboratory research, has a distinct and absolute value. We are also a resource in terms of people. We had a company we started five years ago and they have come back to the laboratory and gathered employees so they can expand.

Now we can look at this in one of two ways: “They’re poaching all of our people! It’s a horrible thing!” Or you can look at it like, “Our people get to go out to industry, have the experience of a startup and in the end, they may not stay in that environment. They may have their thing and then come back to the laboratory and they bring that abundance of experience with them.”

Your technologies are so advanced and complex — was it difficult at first to find local companies for partnerships? When I first came here, they told me my job was to pitch technologies to the Tri-Valley communities and help them be successful. But I found out that we didn’t have a catcher. We would make the pitch and it would go whistling right past and end up in St. Louis or wherever. But we’ve worked here to create and build strong relationships with potential partners, people that have resources, with building up laboratory capabilities and help advise and support and incubate them. So we’re building the catcher’s mitt. I would say maybe 15% of our technologies go to the Tri-Valley.

Are there certain types of LLNL technology especially suited to remaining in the Tri-Valley? We’ve focused on, broadly speaking, advanced manufacturing and life science. There’s a strong nucleus of instruments and electronics, and software development and services. Those are things that resonate well here. Tri Valley life sciences is notably growing. Hopefully, manufacturing will, too. It’s a good thing for the Tri-Valley, in my opinion — a good thing for any region to do that wants to prosper in the future.

How does being located in the Tri Valley benefit LLNL as well? The Tri-Valley is a great place for our staff to live. If they’re happy living here, we’re more likely to retain them. Our neighbors are generally very supportive of the laboratory. We have dozens to hundreds of people that help mentor us and our staff on the business side, and that’s hard to get in a lot of places.

What’s another neat technology you’re working on right now? We have technology that creates these tiny beads, and inside these beads, there’s a processing capability. For example, the beads can capture carbon dioxide, and one of the applications we tried with this was a regional beer brewery. Of course, they let this quantity of carbon dioxide off in the process, and then they have to buy more carbon dioxide to reinject into their product. So there’s an economic incentive and an environmental incentive to capture the carbon dioxide instead.

Another company is creating indoor art pictures that you put on your wall in your office that contain these beads and they help absorb carbon dioxide to make the air quality better.

You began your career as a scientist and inventor. How did you get involved in tech transfer? I became more interested in seeing some of my stuff, my inventions, get to the commercial stage and see the impact. We didn’t know much about tech transfer then, but seeing people all over the place using something I invented that was sort of the hook and I’ve been in the field ever since.

Christine Kilpatrick is a San Francisco-based freelance writer.

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- Location: Livermore

- Description: Multidisciplinary national security laboratory

- Founded: 1952

- Director: Kimberly S. Budil

- Website: www.llnl.gov

- Real estate owned: 7,000 acres

- Square footage: 6.5M gross in its active buildings

- Core capabilities: Advanced materials and manufacturing; high-energy-density science; high-performance computing, simulation, and data science; lasers and optical science and technology; nuclear, chemical and isotopic science and technology; all-source intelligence analysis; nuclear weapons design and engineering; bioscience and bioengineering; earth and atmospheric sciences