Aiming to put the power to shock cardiac arrest patients back to life into the hands of everyday folks, a San Francisco startup closed a $22 million round with the hope of hitting the market this year with a handheld defibrillator.

Avive Solutions Inc. said its automated external defibrillator, or AED, is under review by the Food and Drug Administration. If approved by the agency, the company plans to partner with communities to deploy the device in a unique strategy to increase survival rates for cardiac arrest patients in tough-to-reach areas.

The Series A funding was co-led by Questa Capital, Catalyst health Ventures and repeat investor Laerdal Million Lives Fund.

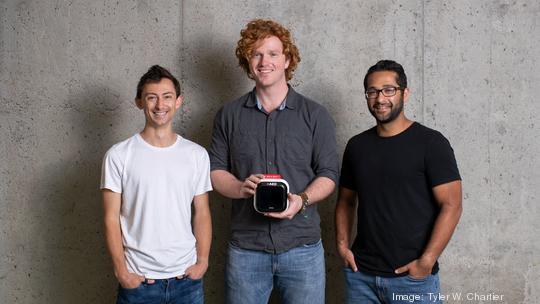

Avive was founded five years ago, after Massachusetts Institute of Technology students Rory Beyer and Moseley Andrews created a defibrillator completely powered by a cell phone. Beyer met Sameer Jafri, the founder and president of the Los Angeles-based Saving Hearts Foundation, a nonprofit focused on preventing sudden cardiac death, at a conference, and the trio ultimately decided to collaborate.

"The whole premise was to make it more affordable, smaller, portable and more familiar," said Jafri, Avive's CEO. "If you can get more devices in the coach's backpack or the glove box, you can give this to more patients."

That mission may be easier said than done. Affordability challenged the goal of Jafri's nonprofit to get more of the life-saving devices into under-served communities; meanwhile, Beyer and Andrews evolved their engineering of complex electronic circuits, powered by a rechargeable, cell phone-sized battery, to deliver a powerful-enough charge to shock a person's heart back into rhythm.

The team's resulting Avive Connect AED — weighing in at just over two pounds — now is in front of the FDA for a decision. Avive has 20 full-time employees and could hit 100 by the end of next year, if the FDA greenlights the device.

Avive's founding trio isn't saying how much the product will cost, but today's four- to seven-pound, bulkier, wall-mounted AEDs, which often found at fitness centers and schools, can cost $1,200 to $2,500. That's not counting the hundreds of dollars it costs every few years for replacement batteries and accessories.

"It will be several hundred dollars more affordable" than the least-expensive AEDs on the market today, Jafri said.

But while size and affordability are important in the potential rollout of the Avive device, the company's distribution strategy may be paramount. It is partnering with five communities so far —including Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, and Jackson, Tennessee — to place the tiny AEDs in at-risk neighborhoods.

Even with the advent of AEDs, many communities remain stuck at 10% survival rates from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, said Beyer, the company's president and COO. In some rural areas, that rate can fall to as low as 1%, Chief Technology Officer Andrews added.

"Some communities are AED deserts," Jafri said. "Within communities there are clear disparities. There are literally parts of a city where zero people have survived over 10 years."

The community partners can deploy Avive's AEDs into small businesses, community centers, even homes.

Those communities are partnering with their 911 emergency systems, thanks to an alliance with emergency response data company RapidSOS. When a call comes to a 911 center, for example, an operator can alert each location with an Avive AED that an emergency is occurring nearby.

Someone can simply pull the device out of its charger and run it to the hotspot, apply the two, sticky electrodes as instructed by audio instructions, put the device on the patient's chest and receive a quick analysis of the heart rhythm and a shock.

If the AED analysis determines a shock isn't needed, the device won't deliver a charge.

Time is of the essence: The average response time of emergency personnel is eight to 12 minutes to get to the scene, and every minute a cardiac arrest patient doesn't receive a shock reduces survival by 7%-10%, Andrews said.

In contrast, a community member toting Avive's tiny AED can shave minutes off the response until emergency crews arrive and stabilize the patient.

Meanwhile, the device can turn over its data to health care providers so emergency medical crews and, later, cardiologists at the hospital can get an earlier deep dive into what was happening with the heart before professional medical help arrives.

"We're not just putting AEDs out there, but we're getting them to historical hotspots where response time is longer," Jafri said, "so you can step up where it counts."