ESS, which raised a quarter-billion dollars when it went public in 2021, isn't the only flow battery company in town.

Portland-based Skip Technology is stepping into the spotlight after six years of quietly working on its own version of the alternative, large-scale energy storage concept.

Skip recently raised $1.3 million, according to a securities filing that dropped around the same time the company announced that the Puyallup Tribe in Washington state had become its "primary investor."

Earlier, Skip won $1.2 million in federal small business technology grants, including a nearly $1 million, two-year award last June.

Denting lithium-ion's dominance

Flow batteries so far haven't dented lithium-ion's dominance as the technology that's helping usher more variable renewable energy sources onto the grid. Wilsonville-based ESS (NYSE: GWH) has been slow to grow and its stock, which began trading at $8.60, has been mired under $1 for months, prompting a New York Stock Exchange delisting warning.

But storage is vital to the grid transition and ESS and other flow hopefuls are banking on providing unique benefits — longer economically viable output chief among them — that figure to become more valuable as renewables' share of the electricity mix rises. Skip's founders say it's uniquely positioned to seize the opportunity after several years of R&D.

"You've certainly seen, in the last 18 to 36 months, a whole wealth of new battery startups as money has flowed into the industry," CEO Brennan Gantner said. "One edge we have is we're now five, six, seven, eight, nine years into this."

Their work, in turn, has yielded several advantages over other flow battery efforts, the company believes.

But first, a brief battery primer.

The lithium-ion batteries now being installed at a furious pace for grid energy storage are in the same broad category of batteries used in electric vehicles, laptop computers and cell phones. They come in a single cell where lithium ions are exchanged through a separator during charging and discharging. Flow batteries, by contrast, work by pumping electrolytes from two separate tanks into a cell divided by a membrane.

The Skip way

Skip uses hydrogen in a gas form and bromine for its electrolytes, which is unusual. (ESS uses iron salts dissolved in water. Vanadium is commonly used as well.) But what most distinguishes Skip is its development of a liquid membrane. Flow batteries have tried various thin-film membrane materials that "could work, could last, or could be affordable," Gantner said, but rarely come through on all three counts. The liquid membrane delivers a trifecta, Skip says.

Not surprisingly, the company's co-founder and president, Ben Brown, an astrophysics Ph.D. and professor at the University of Colorado, is an expert in fluid dynamics.

Gantner also has an astrophysics doctorate. He brings an entrepreneurial background as well, as a co-founder at eWind Solutions, an airborne wind power startup in the late 2010s that he wryly terms "totally a research project masquerading as a business."

The founders, part of a team that now numbers nine, say they've made functioning batteries in their Inner Southeast Portland lab. They expect to begin field tests of a version this year, building toward a 100-kilowatt, 1 megawatt-hour unit. That could power 35 typical homes for 10 hours, Skip says. Lithium-ion batteries typically deliver power for two to four hours.

The Skip units could be chained together to provide more power.

In manufacturing, scaling up is typically a prerequisite to achieving production cost targets, and profitability. ESS has spent much of the past two years developing sophisticated, mechanized production lines, one of the reasons it's been slow to launch into production and sales. Skip is banking on simplified design and a manufacturing partnership to avoid that hurdle, giving it a chance to make money soon after commercialization.

"We don't need roboticized lines, we don't need specialized equipment," Gantner said. "We literally need 3D printers, welders and a lot of containers and a crane."

Puyallup role

Containers because that's where the batteries will be housed. The Puyallup tribe has a shipping container business at the Port of Tacoma, and its deal with Skip includes an agreement to build the flow batteries into the containers.

"We have the facility here in our current place to basically manufacture one battery at a time," Gantner said. "We see ourselves maintaining a single manufacturing line that is iterating and evolving and improving the manufacturing process and the technology. And then we are turning around and taking that learned knowledge up to Tacoma and Puyallup and saying let's bring up your manufacturing, you can adjust and start scaling as we grow in sales."

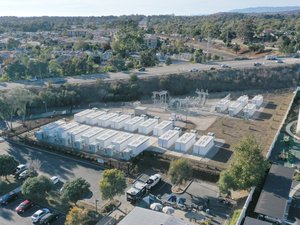

Another advantage Skip claims is a relatively small footprint.

"We have an energy density that's a factor of 10 or higher than other chemistries in terms of actual energy density on the land," Brown said. A couple of Skip containers at a substation could provide the grid benefit that would require three-quarters of an acre from other technologies, he added.

Capital needs

Gantner and Brown are hoping to have an early commercial version of their battery in 2025, but whether they get there or not will partly depend on bringing in more capital.

Puyallup Tribal Enterprises did what's known as a SAFE investment — a simple agreement for future equity — with Skip. That didn't immediately give the tribe an equity stake but allows for one when certain terms are met.

Brown and Gantner say that raising money is more difficult in Portland than it would be if they were based in Boston, a hotbed of energy storage technology. There was just a hint of envy in Brown's voice when he alluded to the progress of high-profile Boston-area startups that have raised hundreds of millions of dollars.

"It's been a slower road because we have not had those huge tailwinds coming out of institutions like MIT," he said.

Sticking with Portland

But both founders grew up in the area and are dedicated to building the company here.

"We think there are huge advantages to doing (the business) here," Brown added. "We've built a unique team here and from that we've met unique partners."

He noted the presence of ESS, lithium-ion system integrator Powin and project developer GridStor as pluses.

"All the parts are coming together," Brown said. "Can they come together fast enough for the kind of timescale that a startup needs to survive? On the other hand, here we are, six years after we first started and we're not just surviving, we're thriving."