You'd be hard pressed to find an Oregon technology company that has had more star turns than Tektronix.

There's the RM561A Tektronix oscilloscope featured in the 1984 "Ghostbusters" film, the 453 model in 1973's "Live and Let Die," the 515A model in 1971's "The Adromeda Strain," and who could forget the 1600 Tek switcher used to fire the Death Star in 1977's "Star Wars: A New Hope."

The website for the VintageTek museum, an on-campus archive of Tek history and promoter of STEM education, has photos from more than 25 movies in which Tek oscilloscopes — with their big knobs, levers and buttons, tiny monitors and squiggly green lines — and other products have been featured, beginning with the 1953 film, the "Magnetic Monster."

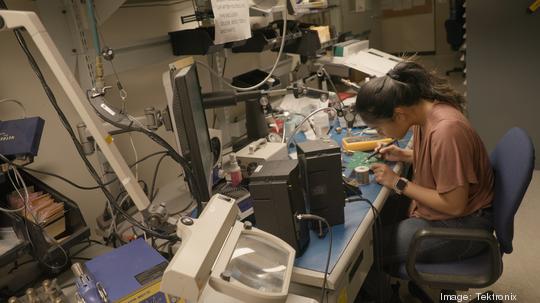

“When I watch Marvel movies, I know I’ve seen our products,” said Natalie Pilar, a hardware design engineer at Tek. “There is something about seeing our name and our products there that gives me a little bit of joy, just knowing that our products are literally everywhere.”

Tek's oscilloscopes and other products allow clients to measure, analyze and test devices across a range of industries, including aerospace and defense, automotive, agriculture, robotics, medical and consumer electronics. And like any good big screen drama, its real world story has had plenty of plot twists, marked by delirious highs and devastating lows.

In the early 1980s, Tek had 24,000 employees. Today, it has 3,500. The company was once laser focused on its test and measurement equipment. It later ballooned into a more unwieldy company that did its own component manufacturing, a move necessitated because of its bleeding edge products. In 2007, it lost its independence when the East Coast conglomerate Danaher bought it for $2.8 billion.

And yet it has survived, for 75 years to be exact. It's been an emotional journey for employees, past and present, and for Oregon tech industry observers. Is Tek a success, a failure, a cautionary tale?

Based on its legacy, the tech talent it propelled and its current business, the answer is all of the above.

Pilar started as an intern at Tek. She joined the company full time about two years ago, after graduating from Oregon State University with an electrical engineering degree. It was the only place she applied. Like thousands before her, she was drawn by the company’s product reputation, the talent it has attracted over the years and what employees past and present describe as a collaborative culture that supports personal and professional development.

To be sure, Tek is a leaner version of its past self. But its contributions to the Oregon technology industry are foundational. InFocus, Planar Systems, Merix, Mentor Graphics and dozens more companies were either founded by former Tek employees or were spun out from the mother ship.

“It seeded a lot of the specializations that we’re good at in the Portland metropolitan area; in semiconductors and anything related to signal processing,” said economist Joe Cortright. “Those all trace their roots back to knowledge that was created here by Tektronix.”

Layoffs and sell offs

The trajectory of Oregon’s technology industry could have been drastically different if Tektronix co-founder Howard Vollum had accepted an offer in the early 1940s to join Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard as they built their company in Palo Alto, California.

Vollum, a highly decorated World War II Army veteran and expert in radio technology, declined, opting instead to start his own company in the burgeoning electronics field in Portland, his hometown.

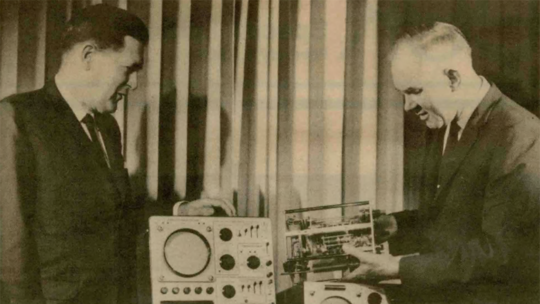

Vollum co-founded Tek in 1946 with Jack Murdock, Miles Tippery and Glenn McDowell. McDowell left, leaving the remaining three founders to grow the business. Vollum focused on technology, Murdock on business and Tippery operations, according to the archives at the VintageTEK Museum.

Tek’s first oscilloscope, the Type 511, shipped in 1947 and became the foundation for other measurement products through the years.

“If you are a biologist, you use a microscope. If you are an astronomer, you use a telescope. Oscilloscope is the instrument that allows an engineer to look into the circuit to see what happens,” said Dave Brown, president of VintageTek and a retired 34-year Tek alum. “You can visualize anything you can turn into an electrical signal.”

The company was an innovator. And not just as it relates to technology. Tek also pioneered a number of progressive business practices. According to Vollum’s 1986 obituary in the Oregonian, Tek led the way with employee profit sharing, growing its executive ranks from within and eliminating the time clock. Employees were on a first name basis and there were no private offices for managers.

Tek went public, under the ticker symbol TEK, in 1963. As the company grew, it expanded well beyond its core product. By the late 1980s, it was still making oscilloscopes, but it was also making logic analyzers, printers, circuit boards, displays, software, video equipment and even its own cabling and knobs.

The company was stretched. A 1990 New York Times article put non-core business losses at $25 million. At the time, Tek was the largest private employer in Oregon, with revenue of $1.4 billion.

To right itself, Tek embarked on a major restructuring that lasted through the 1990s. It spun out its printed circuit board business into Merix Corp., and sold its circuits business to Maxim Integrated Products and its color printing business to Xerox.

“These steps are part of a broad effect to place Tek on a solid financial footing for the long term," Robert Lundeen, Tek's then-CEO, told UPI in 1990. “The best thing Tektronix can do for its shareholders, employees and the communities of which it is part is to return to profitability as soon as possible. Making that happen requires these painful steps.”

The strategy helped boost sales to $2 billion in 1998, but Tek shed thousands of employees through this stretch of divestment. By 1999, it employed 7,500 workers, down 68% from the employment peak of 24,028 in 1981.

"It's just so stereotypical of the way life goes," securities analyst Tom Carley of D.A. Davidson told the Oregonian in 1999. "Things start going south, and you keep hoping, 'We're going to get the turn, we're going to get the turn.' That's human optimism. I think Jerry (Meyer, then-CEO) was optimistic, but it never came. They continued to bleed and bleed and bleed."

Economist Cortright, who has studied Tek's impact on Oregon along with then-PSU researcher Heike Mayer, said the company operated like a research university. A spirit of experimentation doesn’t always support the long-term financial health of a business, he said, though it can certainly attract top talent.

Cortright noted that an argument can be made that without Tek, Intel, which today employs more than 20,000 workers in Washington County, may not have established its first fab here in the 1970s.

Building blocks of an industry

Gerry Langeler is one of many former Tek employees who went on to form or lead other tech companies in the region.

He left Tek in the late 1970s after four years to co-found Wilsonville-based software maker Mentor Graphics with some of his Tek colleagues. He later was managing director of the investment firm OVP Venture Partners.

When asked to sum up the Tek way, Langeler shared a story about how the company used wax paper to separate aluminum dividers, that were part of the guts of oscilloscopes, during product manufacturing.

“Nobody was ever going to see those dividers, unless you took the oscilloscope apart. But Tek’s attitude was, we are not going to have a scratch on the inside of this box. That mindset permeated the company,” said Langeler. “It was incredibly high-quality products and dedication to quality.”

Langeler and other former employees also describe a culture that nurtures talent by encouraging people to move through different business units within the organization. This nurtured professional growth and fostered strong relationships between employees. It's not unusual for Tek alumni to gather for dinners, happy hours and, through 2020, Zoom hangouts. The VintageTek museum is staffed by former employees who donate their time.

Yolanda Green started at Tek in 1977 as a business analyst within the IT department and would spend 22 years at the company. When she left in 1999 for a chief technology position at a startup, she was director of supply chain systems.

“I had really great mentors and people were willing to give me a chance at doing something I had not done before,” Green recalled. She also noted that as a woman of color, she felt supported.

“In my generation you were the first, the only one. No place is perfect, but it was good to see more and more people of color in positions of responsibility,” she said. “It was never enough, but at least there was progress.”

Oregon wasn't on Monique Hayward's radar after she earned her MBA in 1994, but she took a chance when Tek offered her a job. She spent three years at Tek and said the experience laid the groundwork for a 22-year career at Intel.

“I had an amazing boss. He was kind and a smart, intelligent, thoughtful communicator. He showed me how to navigate in a corporate environment and how to do really good stakeholder engagement and stakeholder management” she recalled.

Similarly, Kate Johnson also spent formidable early years at Tek and built a network that would serve her well through leadership stints at InFocus, Jive Software and now as CEO of Act-On Software.

Johnson started her career in accounting at Tek, first in the company’s video and networking division and then in printers. Like others before her, Johnson noted that she was given opportunities to take on new roles and leadership early in her career.

“Oregon tech would not look like what it does (without Tek),” she said. “Tek brought the talent. They are all over the place. A lot have gone on to do great things and in different industries, too. Without that experience and exposure there wouldn’t be as many great leaders in the Oregon tech community.”

Next-gen Tek

The potential of Tek was never something in the past tense, for Tami Newcombe. In fact, it’s the current ownership and structure that drew her to the company in the first place.

Four years ago she was recruited to head up global sales for Tek. As an electrical engineer, she was familiar with the company, and she saw opportunity in the fact that Tek was part of Fortive, a much larger organization.

Fortive was created in 2015 when Danaher split in two. Tek is part of Fortive's Precision Technologies segment.

“For me, it looked like more ‘at bats’ than you would get if you were working for an enterprise company where there is one head of sales, one CEO, one of these top-level positions,” she said. “You come within Fortive and you prove yourself, there is lots of opportunity.”

That has proven true for Newcombe, who two years later became Tek President. In May, her role changed yet again. In addition to leading Tek, Newcombe now oversees Fortive operations in India and chairs the parent company’s inclusion and diversity council.

Tek's sale to Danaher back in 2007 was met with mixed emotions. It gave Tek financial stability, but, it also meant losing a homegrown publicly traded company headquartered in Oregon — a trend that has only continued.

In interviews, former employees said one notable change under new management was an embrace of Toyota’s playbook of lean manufacturing and continuous improvement. This is known as the Fortive Business System and is the playbook for the company’s focus on investments and returns, a stark change from Tek’s historic freewheeling approach to R&D investment.

Newcombe said Tek’s focus on customer needs and innovation is supported by Fortive’s financial resources and balanced by its management playbook.

"As a major player in the Fortive portfolio, it’s exciting to see our own success reflected in the overall health of the company each quarter. It’s also a real asset for us to be supported by Fortive with people and process that foster innovation and career opportunity for our people," she said.

Tek sits alongside seven other companies in Fortive's Precision Technologies business unit, which posted $447 million in revenue for the first quarter of 2021.

According to regulatory filings, the unit had annual revenue of $1.7 billion, $1.8 billion and $1.9 billion for fiscal years 2020, 2019 and 2018, respectively. The company doesn’t break out details of Tek's financial performance but has mentioned it in recent reports. Tek revenue was up year-over-year in the high teens, according to Fortive's first-quarter earnings release; Within China and Western Europe, Tek’s revenue was up more than 20% year-over-year.

“Tektronix has been around 75 years,” Newcombe said. “You can talk about the times that things were awesome. You can talk about the tough times, the acquisitions, the divestures, there is so much history there in the community," she said. "But the one thing there you gotta be super proud of is 75 years later, we’re all still here making our mark and talking about it.”

It's something she talks about a lot.

“The ability to be resilient and constantly reinventing yourself, that is the roots of Tektronix,” she said. “They have always been an innovative company, but to get hit in the face and no matter what to be able to come back, I just think it's fantastic.”

Today, Tek is focused on organic innovation, growing markets that are at technology inflection points, and nurturing the supportive and collaborative culture Tek's co-founders built.

To keep the product pipeline flowing, Newcombe introduced a bimonthly growth board that fuels early stage startup ideas.

Borrowing from — and working with Eric Ries of the Lean Startup methodology — anyone at Tek can come to the growth board with a new product idea. All ideas are welcome: software, hardware, partnerships in either new or existing markets.

The idea gets metered funding that increases as it becomes more fully formed, said Newcombe. Additionally, resources and coaching from Fortive, and the Fortive Business Systems, can be tapped to help determine whether a project should be accelerated or spiked.

Oscilloscopes remain at the heart of Tek innovation. One notable advance is oscilloscopes that are controlled more like a smartphone with pinch and zoom touchscreens and software that sits in the cloud enabling collaboration between globally dispersed teams. Pilar, who is just starting her career at Tek, recalls working on a project in which measurement data could be overlaid in a real world environment using augmented reality.

Tek's market focus these days is on 5G networks and the technological change happening with devices on the edge of those networks.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s a wearable device, a robot or autonomous vehicle, all the electronics, anything that is electronic, we test,” Newcombe said.

Chris Loberg has spent two decades at Tektronix. He said through the upsizing, downsizing, restructuring and ownership changes, exploring and experimenting have remained central to the culture.

“Look inside the company and we are like any Fortune 500 company,” he said. “What makes it fun is having the passion for technology, passion for understanding the customer’s problems and beating the competition.”

Continuing to encourage and harness that passion will drive Tek in the future, Newcombe said. While the company is a much leaner version of what it once was, it continues to have outsized ambitions.

“We have to respect our past, the legacy is real, but we have to innovate our future,” Newcombe said. “You can’t rest on yesterday. You have to push forward. We have a growth strategy that we have to stay focused on. My vision for the company is to deliver best-in-class solutions for our customers and create a diverse and inclusive culture where our employees want to bring their best, every day. Our success metrics focus on customer success, profitable growth and our employee’s experience.”