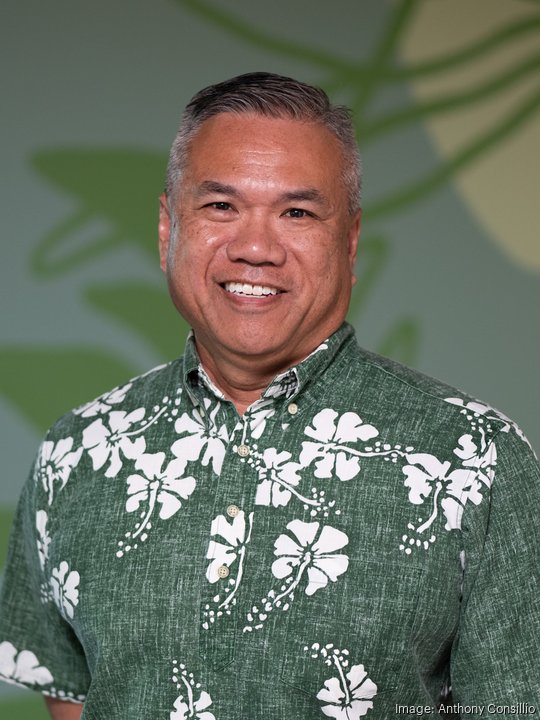

To hear University of Hawaii’s vice president for budget and finance and chief financial officer Kalbert Young tell it, the initial concept for the Walter Dods Jr. RISE Center was “nothing more than a student housing project.”

It all began several years ago, when the former Atherton YMCA went on the market.

The YMCA had been located across from the UH Manoa campus, and UH officials saw the potential from a real estate perspective, recalled John Han, chief operating officer and chief financial officer of the University of Hawaii Foundation. So, in 2017, UH Foundation, a nonprofit fundraising organization for the UH System, purchased the land and the two buildings on top of it for $8 million.

Initially, Han said, the plan “was to add maybe 50 or so beds of inventory to UH housing — so we were going to purchase it, renovate it and then lease it out.”

But as time went on, and the foundation engaged in conversations with UH and the university’s Pacific Asian Center for Entrepreneurship (PACE), a new vision began to take shape — a vision that included new student housing, but was also bigger than that. The concept evolved into what became RISE: a live-work-learn center that encourages collaboration and innovation among its residents.

Han and Young recounted this origin story in a recent interview with Pacific Business News at RISE, which stands for Residences for Innovative Student Entrepreneurs, and opened last August just ahead of the start of the academic year. The six-story facility has 219 rooms — space enough to house 374 students — along with 10,000 square feet of multi-purpose space, which includes coworking and meeting areas, a classroom, a recording studio and prototyping labs.

It’s all designed to “create the next generation of innovative problem solvers,” said Sandra Fujiyama, the executive director of PACE, which runs business-focused educational programming at RISE.

UH, UH Foundation and Hunt Companies Hawaii partnered to design, build and finance the project, marking the first public-private partnership, or P3, housing project for the university, funded by private, non-taxpayer money. Construction costs totaled $77 million, Han said. Funding for construction of the project came from bond financing, a representative for UH Foundation noted.

PBN visited the facility in early April to catch up with Fujiyama, Han and Young, along with a couple of students, about a month before the end of RISE’s first school year.

A new home for PACE

For PACE, Fujiyama said RISE is a “game-changer,” allowing the center to expand its reach and scope.

Launched in 2000 out of UH Manoa’s Shidler College of Business, PACE already had a robust lineup of programming before RISE, including networking events, a speaker series featuring local business leaders, a student-run venture capital fund and the annual UH Venture Competition.

But Fujiyama noted that PACE had largely outgrown its space at Shidler, where it has a 1,300-square-foot coworking center that she said wasn’t enough room to hold growing attendance at many events. Plus, having PACE housed within the business school could be misleading.

“We were bursting at the seams, and then we were at Shidler, so it was limiting the amount of students that were coming to participate in our programs — they all thought we were just a Shidler resource,” Fujiyama said.

Being at RISE, in what she calls a neutral zone, makes it clear that PACE programming is for everyone and can “complement students and what they are learning at the university in every discipline.”

“That is what we really wanted — we wanted to create a diverse environment where students from different backgrounds come together, collaborate, identify things they are passionate about and go out there and solve the challenges that they are seeing,” Fujiyama said.

Another benefit to having a live-work-learn center, she noted, is that students have 24/7 access to resources.

“They can come down and collaborate whenever they want,” Fujiyama said.

In conjunction with RISE, Fujiyama said PACE and UH Foundation raised an additional $10 million — funding that went toward programming, furnishings and equipment for the center, and student scholarships. Those funds were raised from corporate, foundation and individual donors, including Walter Dods Jr., a philanthropist and former First Hawaiian Bank chairman and CEO, who donated more than $5 million and whom the building is named after.

The extra space and funding have allowed PACE to introduce new features and expand upon existing ones.

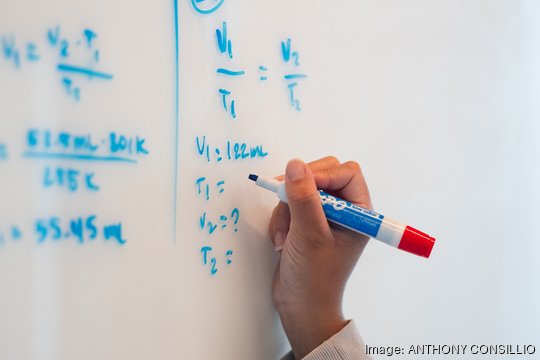

One new initiative is what’s known as the Maker Program, which features hands-on “make-and-take” events where students can learn how to create anything from clothing to a mouse pad. PACE also launched a new funding initiative this year, Kalo Grants, which awards students from any UH campus with grants of up to $1,000 to develop a business idea. To further support business creation, PACE created a new position — an entrepreneur-in-residence — to help students “build an idea,” Fujiyama said. There’s also a new entrepreneurship-focused workshop series covering topics such as pitching an idea and scaling a startup.

PACE also has grown its student group of PACE Leaders from three members last year to more than 40. The leaders help design and execute programming and activities for other students.

Daniella Pasion, a PACE Leaders director who lives at RISE, witnessed that transition. When the team was smaller, she said, “it was really hard to get these events going.”

“Now we are able to expand all our programs and make new programs,” Pasion said. “And we can hold events a lot more often now [and] invite a lot more entrepreneurs into the building.”

Click through the gallery below to see photos of the Walter Dods Jr. RISE Center.

UH RISE Center

Addressing the student housing shortage

What’s now RISE formerly was two buildings: the Mary Atherton Richards House, which was demolished to make room for RISE, and the neighboring Charles Atherton House, also known as “the pink building,” which still stands and has undergone interior renovations to house an Island Brew Coffeehouse pop-up on the ground floor, with a full buildout in the works. Construction on the second and third floors is being completed this month for UH Foundation office space, along with dedicated workspace for PACE students, Fujiyama said.

Even before UH Foundation acquired the buildings, the Atherton YMCA was important to the university. It served as “de facto pseudo inventory for student housing,” said Young. The site offered transitory housing with about 85 beds for rent and, for decades, students who did not get on-campus housing had this at the top of their list, he said.

Ensuring that the “property stayed in the student housing inventory” was important to the university, he said.

Young acknowledged that UH currently “has some issues with on-campus housing,” with a number of structures needing renovations. As the Honolulu Star-Advertiser reported earlier this year, there is a backlog of repairs at student housing complexes on the UH Manoa campus; one complex has even been closed for years.

Plus, what is available on campus is not enough.

“UH has less than 4,000 bed units in on-campus housing at UH Manoa,” Young said. University officials said that at the beginning of each semester in the last couple years, there have been about 750 people on the waitlist for on-campus housing — students who applied for housing but didn’t get a spot. “UH is all full up. … There is way more demand than available supply of housing,” Young said.

“When students cannot get on-campus housing, they end up renting in the open market – which impacts the availability of housing for the general market,” he added.

The university, he said, can help address the problem, at least for students, and he noted that RISE, along with another P3 housing project it is constructing on Dole Street, “are providing base case models that have demonstrated examples that the university … can be successful in redeveloping student housing.”

As of early April, dormitory occupancy at RISE was about 90%, Han said, noting that a similar rate is expected next school year.

Fujiyama shared that the residents come from more than 30 different states and eight countries. Residents range from freshmen to graduate students, with the majority being freshmen and sophomores.

RISE is privately managed by a company called B.HOM Student Living, making it the university’s first housing complex managed externally, UH officials said.

The annual operating expenses for the housing component of RISE are about $2.5 to $3 million, in addition to $4 million in debt service, Han said.

“The way that we built this model is to build enough beds … that we could cover the debt service of the bonds that were issued to build the building,” Han said.

Young emphasized that none of the operating expense is coming from the university. The cost that students pay to live at RISE, along with commercial lease rents, cover the operational expenses.

Young said that, compared to their university-owned counterparts, this model of housing has a number of other benefits, including “reduced capital funding into the projects … and due to the financial incentive of the private partner, the properties are apt to stay in better condition for tenants.”

Plus, he continued, “private development can be more expedient to execute than public-works projects — RISE has demonstrated that, and the P3 structure also allows for the university to assign operational risks to the private partner — i.e. occupancy, rate setting, maintenance, etc.”

Helping students ‘hit the ground running’

According to university officials, RISE is only one of a handful of such residences across the country, and they cite Lassonde Studios, a student entrepreneur housing center at the University of Utah, as an inspiration for amenities and programming. At Lassonde, Fujiyama noted, they “really wanted the students to own the space,” so — in keeping with that model — PACE staff don’t have offices at RISE, except for one room they use when running events.

On the day PBN visited, there were a dozen or so students in the common area on the bottom floor — individuals were studying, small groups worked together, and the entrepreneur-in-residence was posted up at a table where students occasionally dropped by to chat.

According to Pasion’s account, it seems this type of activity is pretty constant.

“There are always people out there studying, doing work or even just talking and playing games,” she said. “… Even at nighttime, there are still people studying here and I’ll come down just to say hi to my friends.”

Pasion is a senior who is majoring in marketing and entrepreneurship — and she already runs her own business that creates car accessories. It started as an online venture and she’s recently expanded to pop-ups. After she graduates at the end of the semester, she hopes to work at a tech company, or maybe start another business.

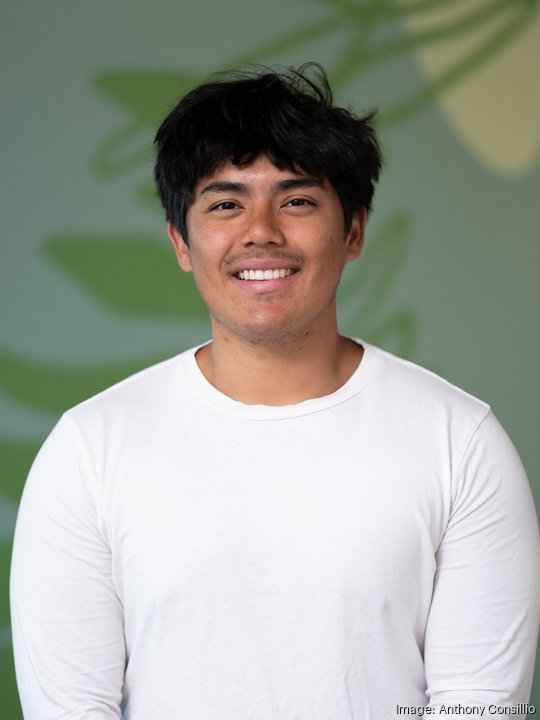

Maverick Tongg is a sophomore RISE resident who’s also a PACE Leader. Though he’s still early in his college career, Tongg already knows that he one day wants to start his own business, and he said he chose to live at RISE to gain skills to help him do it.

But having aspirations for a career in tech or entrepreneurship is not a prerequisite to be a RISE resident. Living at RISE is available to students of all majors — a purposeful decision that Fujiyama said is crucial to the ethos of the facility.

“For us, it is incredibly important to have diversity — in order to make a successful team, there needs to be diversity. … The engineering student might come up with the idea and the business student will know how to market it, and maybe we need the science student to build whatever it is,” Fujiyama said.

As far as what types of innovation UH officials are hoping will come out of the space, Fujiyama said it’s more about “meeting the students where they are at” and helping them pursue whatever it is they are interested in.

While it’s tough to measure exactly the number of new ventures that have been created as a direct result of RISE, the university has data comparing annual student engagement at PACE pre-RISE, and as of February 2024, seven months since its launch. According to the data, 115 teams and ideas were generated in the first seven months of RISE, up from 60 teams in pre-RISE years. PACE programming also attracted more than 825 students in that seven-month period, up from 600 in the pre-RISE annual average.

Ventures that students have created this school year include an app designed to address food insecurity and a company that utilizes artificial intelligence to improve energy efficiency in buildings.

But when it comes to workforce development, the goal of PACE and RISE is broader than students launching startups.

In conversations she’s had with local businesses about what they are looking for in new employees, Fujiyama was surprised that some cared less about any specific technical skills and more about soft skills — things like critical thinking, collaboration and effective communication.

“I think with how the world is changing and how technology is changing so quickly … having those skills is what is going to distinguish you from the rest of the folks,” she said. “Can you work with people? Can you recognize people’s strengths and your weaknesses and then come together to work on a project?

“It’s not easy — it’s a difficult thing to work with people from different backgrounds or people you don’t know. But that is what you have to do in real life. That is what we are trying to build, so they can hit the ground running when they enter a job.”

Going forward

Looking ahead, Young said he feels that RISE can help address larger student housing issues by serving as a development model for future projects. He noted that RISE, as a privately owned and operated entity, “is significant for the university, in terms of what we are going to be doing moving forward.”

“There are very significant portions of this project that will be applicable and replicable to other facilities and projects that the university will develop,” he said.

For Fujiyama, she sees RISE as having a prominent place in the state’s overall innovation ecosystem — a tool that can help create jobs and diversify the economy.

“We want to be the location where people come, where they can convene, where they can connect, where they can build relationships and we can come together as a community to work on the challenges that Hawaii has,” Fujiyama said. “[We want] to be this local innovation hub … [where] we can work together to address challenges and come up with solutions.”

Of course, alleviating the housing shortage and bolstering Hawaii’s innovation ecosystem are large, sweeping goals — the results of which can’t be seen immediately.

For now, the impact is perhaps best seen on the individual level, in the students who are a part of RISE.

Pasion said that being at PACE and living at RISE has given her “a lot of confidence to be an entrepreneur.” Having the opportunity to meet established business leaders, in particular, has helped her see a path for her future.

“Hearing stories from all of these entrepreneurs in the community, it feels relatable because they are just like us — they had an idea and then they grew their business. So it’s like I can do that, too, which is really cool,” she said.

Tongg said he used to have “a lot of limiting beliefs” about himself and what he is capable of. That’s changed this year.

“Being in this program and being at RISE has been able to just change my belief in what I can do,” he said. “And so going forward, having that belief in yourself — that you can do it — is something you can’t take away from somebody.”