Louisville researchers-turned-entrepreneurs are freeze drying blood to increase its shelf life.

Blood in its liquid form has a shelf life of 42 days, and it rapidly degrades if not stored at a correct temperature. This creates problems in instances where there is frequent blood loss and a lack of time to administer it or in times of a blood shortage, which the pandemic has created.

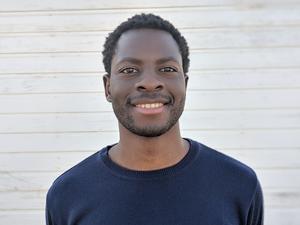

Desicorp is looking to solve for that challenge with a freeze-dried blood that can be rehydrated when needed. The company was founded in 2017 by three academic researchers with ties to the University of Louisville, including Michael Menze and Jonathan Kopechek. The third co-founder, Brett Janis, serves as the company’s CEO.

Desicorp’s product can last up to three years in terms of maintaining its structure and six months in terms of its function. In appearance, the freeze-dried blood resembles paprika.

“The goal is to have this be available anywhere there is a patient, no power required, no cold chain,” Janis said.

Though the product isn’t launched yet — it is still pending regulatory approvals — Desicorp has raised about $500,000 in funding in a pre-seed round. It’s in the middle of another fundraising round, but Janis said they have it handled and are being selective in who they choose to add as investors. It’s waiting for contracts to come in before starting additional fundraising efforts.

“It’s a nice position to be in, because we got into this, not to make a bunch of money, but we saw how long it could take academia to generate a product,” Janis said.

Desicorp previously held a contract with the United States Department of Defense, and it is currently collaborating with other businesses and military research institutes, which Janis couldn’t yet name.

The military has a strong need for blood components, many survivable battlefield deaths have been caused by blood loss, Janis said. In times of conflict the blood could also be administered to civilians. But even outside of the military, Janis said the product can be used for things like postpartum hemorrhage.

In rural and remote areas, there is a need for increased blood supply as well.

“They don’t have blood on site because the populations are low enough that they don’t have a donor supply, and they’re not equipped necessarily,” Janis said. “Because after 42 days, the blood will expire, and the blood system in the United States is built around not wasting blood.”

The pandemic also caused the amount of blood donations to decrease. One of the benefits of being able to increase blood’s shelf life is the ability to create a stockpile of it in the event of another pandemic.

Desicorp employs four people, including Janis and James Welch, director of research and development, and engineer and technician, respectively. By the end of the year, it plans to add two more, and by the end of 2023, it expects to employ 12 people.

Beyond its employee base, the other founders are consultants on the business, and other leaders from the community — including those from Louisville-based accelerator XlerateHealth — serve on the board.

Desicorp leases about 4,000 square feet of lab space in the One Innovation Center, 201 E. Jefferson St. That center also houses office spaces for the Louisville Healthcare CEO Council.

UofL owns a patent on the product’s loading device, and Desicorp has patents coming out on its innovations on the process. It has an exclusive license on those patents.

Welch said it’s beneficial for Desicorp to be headquartered in Louisville because all of its founders live there. He also pointed to the UPS World Port being a key selling point for the city.

Desicorp isn’t the only entity working in freeze-dried blood, but it is one of the only ones in the space that does work on red blood cells. Welch mentioned others work in freeze-dried artificial plasma and platelets.