The key to surviving heart failure could lie with an obscure pathway inside the human body – and a drug hiding in plain sight.

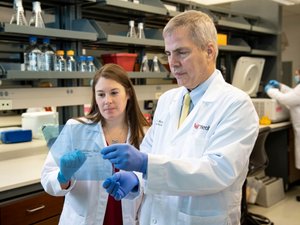

A clinical physician at the University of Cincinnati and a veteran of the pharmaceutical industry are hard at work transforming that possibility into a company both believe could be worth billions.

“It’s difficult for me to oversell how big of a deal this is,” UC cardiologist Dr. Jack Rubinstein told me. “It’s millions and millions of people worldwide. It will change the paradigm of how heart doctors see heart patients. It’s a true game changer.”

Rubinstein has been working on the drug, probenecid, for 15 years. He likely wouldn’t have met Fred Sexton, nor co-founded with him the nascent pharmaceutical company advancing headlong toward clinical trials, were it not for a chance game of polo in Cincinnati.

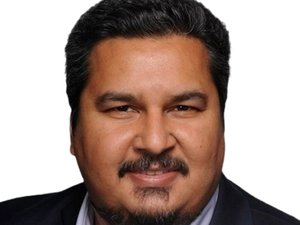

Rubinstein admiringly calls Sexton “a drug development guy.” In fact he’s a four-decade veteran of the field who’s held multiple senior management positions at the biggest names in pharma.

In 2021, a retired but amply busy Sexton was shuttling between his Florida home and Cincinnati, where he advises a “leading edge” company he declined to name, when he met Rubinstein, a Mexican-born cardiologist freshly dismounted from a horse – and glistening like a Greek god, Rubinstein recalled laughing – at the Cincinnati Polo Club.

“We started talking just basic science and whatnot, and I said, ‘Shoot me some of your papers,’” Sexton said. “Long story short, I called Jack and said, ‘You’re sitting on a rocket ship here. We’re starting a company.’”

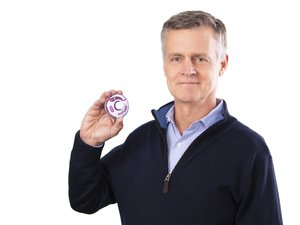

Fewer than three years later, TRPV Pharmaceuticals is on the launch pad amassing A-round venture capital financing. The company signed a licensing deal with UC in early 2024, and if the financing round goes according to plan, it could begin phase 2 clinical trials by the end of 2024.

Sexton, now CEO of the company, is tight lipped about the financials – he declined to disclose its valuation – and avowedly cautious in his projections.

“Having said that, I do believe 60 months out that you’re well into $1 billion in sales,” he said. “In terms of revenue potential, it’s a multibillion-dollar drug just based on U.S. sales alone.”

As for the company's future location, Sexton said it could position multiple states against one another in a battle of tax credits and other incentives.

“So if Ohio’s business development group wants to be aggressive and wants us to come there, we can have those conversations,” Sexton said. “But there are a lot of states that look for and work well with companies like this that, at the appropriate times, we can have those conversations.”

The ‘aha!’ moment

It would be very good for the 6.5 million adult Americans who live with heart failure if modern medicine had a safe and viable way of making the heart contract better. That’s what heart failure is – your heart loses contractility, so it pumps less and less blood to the rest of your body, causing all sorts of issues over time, including death.

Right now, that drug doesn’t exist. With rare exceptions, cardiologists treat heart failure in every way they can except by improving contractility – and it’s not for Big Pharma’s lack of trying.

“None of the medications developed have ever helped a person live longer,” Rubinstein said. “It makes them feel slightly better. It might get them out of some trouble. But by making the heart work harder, they actually increase the chances of the person dying. We almost never use them – only if we have to. Every time we try to improve the way the heart contracts, we cause more damage.”

Probenecid has been around since World War I, when the U.S. government developed it to stretch out supplies of penicillin. Rubinstein calls it “the Forest Gump of drugs,” because it began showing up with remarkable frequency as its applications multiplied – it’ll get you banned from the Olympics because it can hide steroids in your urine, for example. The drug last gained popularity as a gout treatment but has largely fallen out of favor, according to Rubinstein, such that few doctors care to study it in detail.

The UC doctor sought to rescue probenecid from obscurity starting around 2009, his interest piqued by research “in the back woods of science” on a family of ion channels in the body called TRPV channels.

Think of TRPV channels as password-protected doors that, when opened, allow for a slew of things you might take for granted. The channels allow communication between cells, letting certain parts of your body know now is the time to activate… something. TRPV 1, for example, gives us the sensation of spiciness.

Dr. David Julius, a researcher at the University of California, San Fransisco, discovered TRPV channels in 1993 when he cloned and characterized TRPV 1. Julius didn’t focus on the other three TRPV channels, though years later, a student of a student in his lab would test all the TRPV channels against different molecules and find probenecid opened up TRPV 2 channels. They didn’t do anything with the discovery, but Rubinstein took notice.

“I remembered this drug from my school days, and I went to dig into it,” he said. “A student of mine, now my colleague, Nathan Robbins, looked through the history of medicine, and it turned out in 1955 there was a paper that actually showed probenecid actually improved the function of the heart, but they didn’t understand what was happening. They couldn’t tie the two together, because they couldn’t. That was the ‘aha!’ moment.”

Rubinstein discovered TRPV 2 was “crazy expressed” in the heart. “Nobody knew this,” he said. Probenecid hits the channel to let calcium in, calcium in the heart being like gas in your car engine – which is it say, it makes your heart contract better.

Julius won the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2021 for his discovery of the TRPV channels. Around the same time, a paper emerged from Harvard Medical School’s Brigham and Women's Hospital. Researchers used the Medicare database to compare probenecid to other gout drugs and found the same thing: Probenecid improved heart function.

“They were scratching their heads, because that wasn’t supposed to happen,” Rubinstein said. It would take an editorial from Dr. Michael Givertz, head of heart transplants at Brigham and Women’s, to explain the role of the TRPV 2 channel. By that time, UC had already obtained patents for the use of probenecid to treat heart failure.

Rubinstein met Sexton months later. Sexton had “virtually zero” knowledge of TRPV channels beforehand, but the Harvard paper sealed the deal for him.

“When I looked at that data, I said, ‘We can do this, this is a sleeping giant,’” Sexton said. “People haven’t paid attention to it because the molecule is relatively old. The benefit, though, is the molecule is extremely well understood and safe, and that makes the difference.”

'We're ready to roll'

Geoffrey Pinski, assistant vice president for technology transfer at UC, helped Rubinstein to file for intellectual property protection beginning in 2012.

“We’ve been going back and forth for nearly a decade trying to make sure the patent position is as strong as possible,” Rubinstein said. “Geoffrey and his team have been with us through thick and thin.”

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office approved a pair of patents in 2020. The first patent covers using probenecid to treat heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, the most common kind of heart failure. The second patent covers using probenecid to treat acute decompensated heart failure, or the sudden onset of severe heart failure symptoms that can be fatal.

Probenecid is a generic drug available for pennies, according to Rubinstein, with no intellectual property attached to it. Cardiologists could prescribe it off-label to heart failure patients without issue, especially prior to UC’s patents. Whether cardiologists can do so now – or whether UC and TRPV Pharmaceuticals have legal recourse in light of the new patents – remains unclear.

Sexton declined to comment on the matter, though he did say TRPV Pharmaceuticals’s approach and dosing mechanisms will differ “significantly” from the fixed-dose oral solids of probenecid on the market today.

“We’re not trying to do the generic drug. That will be used for treatment of patients with stable heart failure,” Rubinstein said. “But there’s so many different kinds of heart failure and all kinds of ways of making the drug to make it better for certain patients at certain times.”

Sexton declined to disclose the details of the licensing deal with UC but noted they differ from UC’s standard licensing agreement.

He confirmed the TRPV Pharmaceuticals is still having “meaningful conversations” with UC about building out its patent portfolio. “And then, anything that we do on our own is ours,” he said.

“As it relates to probenecid,” he added, “if it’s sold out into the market for this particular set of indications we have, UC is a beneficiary of that, and anything that we do independent of UC that just adds additional patent protection, UC is a beneficiary of that, because it just extends the patent life of the (intellectual property) that you license from them.”

TRPV Pharmaceuticals lists six indications for which it could eventually pursue clinical trials and, ultimately, FDA approval, including use of probenecid to treat strokes. The company could also branch out into other activators of the TRPV 2 channel, including cannabinoids, which Rubinstein’s lab at UC is currently studying.

But, as Sexton often says, “you have to walk before you can run.” Hence the company will first focus exclusively on clinical trials for acute decompensated heart failure.

“That’s where we can save people who are about to die,” Rubinstein said. “From there, we can tailor the approach out of the generic into something more specific for people who have a kind of heart failure different from stable heat failure, and that’s millions and millions of people. That’s the needle we’re trying to thread.”

Sexton has spent significant time since meeting Rubinstein lining up the supply chain to manufacture the drug in advance of the clinical trials.

“We’re ready to roll,” he said. “This is very simply about raising enough capital to get us phase 2B, at which point we’ll have a positive signal, and we’ll be able to set the cardiovascular world on notice.”