On a stretch of ice and snow in Antarctica’s Atka Bay, a yellow vehicle the size of a car for a small child slowly rolls up to a group of emperor penguins. The four-foot-tall birds peer down at the unattended vehicle as it pauses nearby on the white terrain. A few penguins might waddle over for a closer inspection.

The penguins, which have no land predators, are more curious than frightened of the colony’s new addition, as long as it doesn't move too fast, explained Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution’s Daniel Zitterbart.

Zitterbart is just one of the scientists at Woods Hole on Cape Cod using robots to study the natural world in an effort to reduce animal-human interactions, collect more fulsome data and reach inhospitable locations. Antarctica and the ocean’s coral reefs are just some of the places that scientists are deploying these new, autonomous robots.

“The cool thing now is that robotics is making its way into these very, very remote areas of the world,” Zitterbart told BostInno. “I think robots can change the way we interact with large groups of animals in very remote areas of the world because they have the time. They are not dependent on resources, and they have less impact.”

On the ice

Zitterbart and his team are developing an Antarctica-traversing robot, nicknamed ECHO, at Woods Hole. They have several global partners involved in their multi-year study of penguins in Antarctica, including the Centre Scientific de Monaco, CNRS Strasbourg, Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nuremberg and Alfred-Wegener-Institute’s Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.

For the last few years, members of this team have spent eight weeks at the bottom of the globe each year placing RFID chips in about 300 chicks. ECHO is essentially a mobile antenna, Zitterbart said. It will drive around and scan the penguins to determine the size of the colony and see which chicks return.

ECHO took its first test run at the end of last year. Right now, the robot still needs supervision and to learn simple tasks, like driving itself to the observatory to recharge.

“My hope is that we reach real autonomy and year-round operations in about three to four years,” Zitterbart said.

Over the course of several decades, Zitterbart and his colleagues hope to track how long penguins live, their breeding habits and what influences its survival.

“We want to do this in light of the coming environmental global change. Antarctica is going to change,” Zitterbart said. “Our penguins will have to adapt to that at some point. We don’t know how much. But we also don’t know how good they are at adapting.”

Under the sea

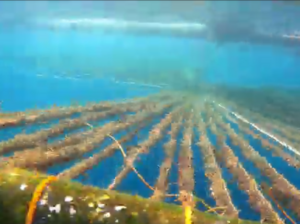

Thousands of miles away in a decidedly hotter climate, Yogesh Girdhar is deploying a robot that swims rather than rolls. Girdhar, an associate scientist at Woods Hole, is working with researchers at Syracuse University to develop a robot that autonomously navigates coral reefs.

Without robots, Girdhar said, this research would usually be conducted through more invasive means: either by human divers, or by dropping a net into the ocean and seeing what marine life it pulls up.

The robot they’re testing in the U.S. Virgin Islands will measure the biomass, biodiversity and behavior or life in coral reefs.

“We want to understand the coral reef habitat and be able to detect the anomalies in there,” Girdhar said. “We’re hoping that these anomalies might correspond to, maybe, early cases of a disease. Can we detect a disease when its infancy so maybe we can take an intervention early on before it spreads to other corals?”

Girdhar said while they’re working on algorithms to make the robots fully autonomous, they now keep it on a leash just in case.

Rise of the robots

The use of robots to capture data in the natural world isn't new. Zitterbart said robots that scan the open ocean have been active for about 20 years. But ones that can navigate in close quarters with animals and plant life and make their own decisions have come about recently.

“It’s just emerged because artificial intelligence algorithms got so much better in the last decade. Now they’re not only better, but they’re also (using) much less power,” Zitterbart said.

The goal is not just to use ECHO to minimize the impact on the environment and penguins. A robot is also better at scanning thousands of penguins year-round than a human.

“We want to do more science with less impact. That kind of drives everything,” Zitterbart said.

Girdhar said that robots also take on risk that would usually fall to human researchers.

“The things we don’t know about, we don’t know about because they’re hard to observe. So that’s where you need the robots,” Girdhar said.

Girdhar said the field is still in its early stages. Most robots, including those Woods Hole is using in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Antarctica, are still being tested and developed. Research is ongoing to determine how animals react to the robots and the best way to make them unobtrusive.

Yet once they’re in the field, the data scientists have to work with could skyrocket.

“The science we do is totally dependent on the data we collect. Robots allow us to collect many different types of data sets,” Girdhar said. “The data basically can open doors to discover new science.”