"Over 50% of all water projects fail," Shannon Evanchec, co-founder of TruePani, tells me.

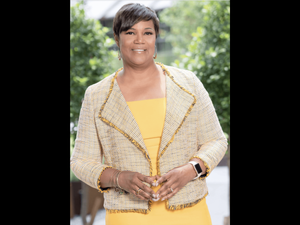

Seated in a lounge area at the Peachtree Corners incubator Curiosity Lab, where TruePani's office is located, we're chatting about Evanchec's experience as a young, female entrepreneur.

Evanchec started TruePani, a company working to reduce environmental contaminants and improve water quality and other cleantech issues, while attending Georgia Tech as an undergraduate. A mural created by Greg Mike, a local graffiti artist, is situated behind her. The words "Dream," and "Build," stand out.

"Name me five of the most successful female entrepreneurs you can think of," she says.

Sara Blakely, the founder of Atlanta-based women's shape-wear company Spanx, comes to mind immediately.

"The second one is probably Elizabeth Holmes, the founder of Theranos," she laughs. I nod with a knowing smile; Holmes, once one of the world's youngest female billionaires, is now facing criminal charges and up to 20 years in prison for the false claims she made about the capabilities of her blood testing technology.

Evanchec then reveals she's thinking of dressing up as Holmes for Halloween. With a feminine face, bright eyes, a wide smile and blonde locks, Evanchec could pull off the look with a bun and black turtle neck, no problem. That's where their similarities begin and end.

I joke that she'll have to walk around all night speaking in an unnaturally deep voice.

We then get onto the topic of the recent buyout of WeWork founder Adam Neumann, who left the company during financial trouble with a $1.7 billion golden parachute to cushion his fall. This week alone, the company was acquired by SoftBank but has postponed thousands of layoffs due to the lack of liquidity to pay workers severance. Evanchec questions aloud how much of a difference there is between Neumann and Holmes, aside from gender and their industries.

I think it definitely could have been avoided, and I hope my story helps other people avoid it.

Evanchec, who grew up in Pennsylvania and moved to Atlanta to attend Tech, isn't like Neumann or Holmes in the least. But like them, she's experienced success and failure.

Her startup went through the CREATE-X program, an initiative at Georgia Tech that helps students develop startups with funding, mentorship and other assistance. During her time at Tech, TruePani won the InVenture Prize People's Choice Award, which garnered a significant amount of attention to their work.

But shortly following graduation in 2016, Evanchec faced challenges no one had warned her about. The problems that could have derailed her mission and shuttered her business forced Evanchec to do a complete 180 and pivot her business. As part of American Inno's Autopsy feature, where our writers across 14 markets hold an honest Q&A with founders about their failed businesses and ideas, I sat down with Evanchec to learn how it all happened.

"After going through all of this, I really understood the phrase, 'ignorance is bliss,' and I totally believe that now," she said. "I was pretty cynical and jaded after all of this for a while."

Q: Why’d you launch the business; what did it do?

"We launched TruePani because at the time, myself and my co-founder were working in a water quality lab at Georgia Tech. Long story short, the field portion of that was in rural India. And we noticed this problem: the water that people were accessing ... wasn’t the same quality as what people were actually drinking. We traced it down to a cup level where people would have these stainless steel cups in their home and we brought in sterilized water from the lab, poured it into the cup, immediately tested it from the cup and found E. coli in over 90% of samples collected. People are paying---nonprofit organizations, government organizations are paying to put wells or some type of intermittent water supply system in place to get people safe water, but by the time they drink it, it’s not safe. From our engineering mindset, A doesn't equal B here, and this outcome isn’t what is intended, so let’s create a solution that protects that system and makes sure water is safe when people drink it.

From there, we had some great advisors at Georgia Tech who gave us a little flexibility and freedom in terms of researching solutions to this problem. And so we spent some time researching solutions and then entered the InVenture Prize competition at Georgia Tech, which is the nation's largest undergraduate invention competition. Through that process, we developed this device which looked like a lotus flower that used copper as an anti-microbial mechanism to kill suspended microbes in stored drinking water supply.

We ended up making it to the finals of the InVenture Prize and competed in that competition alongside five other teams and ended up winning the People’s Choice Award. So because we won that, all of a sudden we had some money and then we had people sending us emails and seeing if we would join the CREATE-X program. We were graduating at the time, we had a little bit of funding coming in, we got accepted into the CREATE-X program and we said, 'Let’s try this out, because why not? The timing is never going to be better to work on this project.'"

Q: Biggest Milestone / Success?

"Our biggest milestone was conducting and finalizing our pilot/proof of concept study in rural India in late 2016. We partnered with an organization called Year Out India, which was on the ground in rural villages in India. They employ people from the village to get a more in-depth understanding of the perspectives of people living in the area. Through that partnership we deployed a batch of these devices that we created and spent a month going to people’s homes every day and collecting water samples to get data on how it worked in the field. And that data was really promising; we found about a 97% reduction in E. coli compared to homes that didn’t use the device.

Then coming off of that high, we also started to realize that we had only been focused on this one, narrow focus of, 'Can we get this to work?' And we hadn't thought about what happens if we do get this to work.

Then coming off of that high, we also started to realize that we had only been focused on this one, narrow focus of, 'Can we get this to work?' And we hadn't thought about what happens if we do get this to work. How would we ever finance this? How would we ever get people to adopt the technology if we’re not in their home every day making sure that they're using this technology? We started to understand a lot of different perspectives around how people view their water.

One area of this particular village lived at the base of this mountain that translated to mean, 'temple mountain,' so they thought all their water was better because it was coming off of this holy mountain. Breaking through this idea of what people think about their water vs. what it is in reality was something we started to realize was a huge barrier. Also, the distribution channels and all the economics behind producing this device---would it be cost effective and more effective scientifically compared to alternatives on the market? When it comes to water and sanitation everyone wants to invent the next new thing, but what we really need to do in that field is think about what has worked and how we can iterate on that.

You have all these things that engineers are thinking of but not understanding how people are going to interact with it in the real world and how people would go about solving this problem for themselves if you gave them the tools to do so. I think it's really important in water and sanitation so you're not just coming in as an outsider forcing this device on people. That wasn't really something we had thought about until we were there experiencing it ourselves, which is why I like to talk about this. You have so many people with good intentions, whether its a church group, a nonprofit, a mission trip. We really need to understand from people who live this day-in and day-out what their perspectives are before we come in and try to tell them what they should be doing and change that way of life. And making sure that we have people that have the technical and the business skill sets to work in these areas is really important, too, because intention doesn’t equal impact."

Q: A year before pivoting, describe the state of the business/brand.

"We had taken a step back from the company and we were in a research mode of understanding what we had worked on, what did and didn't work and if there was any path forward.

We started the business and officially incorporated in mid-2016. At the end of 2016 and into early 2017 ... we had been completing the pilot study and then analyzing all of the data that we had collected from the pilot study and publishing our proof of concept validation report and getting feedback on it from people in the industry.

Doing a startup right out of college is a pro, but it’s also your biggest con.

That’s when this lightbulb was going off. We had really only had one person give us this feedback before we realized it for ourselves. We started to go through this realization process and reach out to more people we knew would be critical of what we were working on to see if there was a path forward. We ultimately realized that there wasn’t a path forward with the technology that we had created at that point in time that would have an impact that we would be proud of.

We kind of had this downtime in the second quarter of 2017 where we were thinking, 'What are we going to do and do we keep going with this?' We had some money still in the bank and we had a passion for wanting to solve this problem between source water and point-of-use drinking water and we just really didn't know what to do. We still wanted to keep researching and understanding what the next step could be. At the time, I got a job with a civil engineering company out on this construction site and I would go out and be the civil engineer on this construction site from 6 a.m. to noon every day and I would come to the office and work on TruePani in the afternoon. We really took some time to dig in and research and explore other options. It was during that period in time that we really started thinking about lead in drinking water in the U.S.

Q: So. What happened?

"Ultimately what made us pivot is we just didn’t want to quit. We had a little bit of money left in the bank, and we just had this drive. At this point in time, we had been through the CREATE-X program, we had made so many connections in the Atlanta startup and Atlanta social entrepreneurship community and we didn’t want to let that go to waste. We started trying to figure out what was the root of the problem that we were going to solve. We really kind of came to lead in drinking water for a couple reasons. One, when we first started working in a water quality lab was when the Flint water crisis kind of hit the news in 2014. When we had been working on this project, the whole time, people were asking us, 'What about Flint?'

We were working on E. coli in India. This is lead in drinking water. It's totally different. It’s water, but that’s really about it, it's completely different outside of that. But we started looking into how does lead enter the drinking water supply in the U.S. It's such a last mile problem that parallels itself so well to what we were working on in India. You have the source water that is likely safe in India. Then you have water stored in people’s home that's contaminated. Here in the U.S., we have water leaving the drinking plant that's, let say 99% of the time safe, outside of anomalies where water utilities mess up ... but then we have this plumbing infrastructure network that could literally be contaminating our water as its coming out of our tap ... That problem really was something that struck us that we decided we wanted to figure out a way to address that and that’s when we decided to pivot."

Q: What were some early warning signs?

"I think the early warning signs have been more clear now that we are where we are with TruePani today. The first thing that we did after we pivoted was we talked to everyone that was anyone in the lead in drinking water space. We looked at every peer-reviewed piece of research and we reached out to the people who had written those articles and done those studies. We talked directly with someone that worked on writing the lead in copper rule who was on the EPA task force. We gleaned a lot of insights from a lot of people who were a lot more experienced in this area. We didn’t do that at all the first time.

You have to have thick skin doing this

I think that’s really important. One of the things that I always say is, 'Doing a startup right out of college is a pro, but it’s also your biggest con.' The pro of it is you're used to living like a college student, you can take this risk, you don’t need the income you would need to support your family later in life or anything in life. That is an asset. The disadvantage of it is you don't have 20 years of industry experience and you're kind of going at this blind. What really worked for us the second time was being really transparent about what we did and didn't know and looking to people who had a lot of experience to guide the way. We didn’t do that the first time because we were so singularly focused on, 'Can we make that thing that works?'

Q: Could the end have been avoided? How?

"I think it definitely could have been avoided, and I hope my story helps other people avoid it.

We've talked to students who are now working in water and sanitation at Georgia Tech and other universities as well to share our experience with them. Hopefully, they don’t have to go down the path that we went down to figure that out themselves.

When it comes to water and sanitation specifically there's a lot of resources out there. One is Improve International, which compiled all the failure statistics around water and sanitation projects. There really isn’t a reason to go down this road as an individual. There's so many resources and people willing to talk to that you can access before you make the mistakes that we did.

Q: If you had to in just two sentence, what would you label as the cause of pivot?

"I always say now, 'Know what you don’t know.' Figure out what the questions are and figure out what those answers are by talking to people."

Q: How did this experience personally affect you outside of the office?

"You have to have thick skin doing this. One of the things that I always say is, 'You can’t get too high with the highs, and you can't get too low with the lows.' You are essentially becoming your work. There’s not necessarily an 'off' button. It's not like you leave the office, go home and then don't do anything until the next day. It’s constantly on your mind. You’re thinking about it when you go to sleep. You're thinking about it when you first wake up. Having a separation between who you are as a person and what is happening with the business is something I had to learn. I would let my emotions get tied up in my sense of self or how the business was doing."

That type of mindset is really important---knowing that you can try something for a little bit and it might work and it might not, then you go try something else but it’ll be fine. That’s life.

Q: What were your biggest lessons learned from the experience?

"Talking to people and having a better understanding of the background and what you don’t know. It’s okay to be wrong and it’s okay to try things and to fail at them. I think we get so caught up in not talking about failure and that's really a part of life. You have to be able to know you're going to land on your feet and be able to come back and try something again. It might work and it might not work. That type of mindset is really important---knowing that you can try something for a little bit and it might work and it might not, then you go try something else but it’ll be fine. That’s life."

Q: Describe your current bustiness through the lens of the previous one; what’s different?

"The biggest difference is we have a broader perspective of everything that goes into having a successful business. We care more about numbers than we previously did because we had just gotten to the stage where we were trying to essentially commercialize the technology. What we've done now is figure out first what’s a problem we’re trying to solve and how can we solve this in a cost-effective way that's going to have a benefit to us but also to our customer. Having that shift in mindset and understanding more of what a sustainable business model is, is something that is different."

It’s okay to be wrong and it’s okay to try things and to fail at them.

Q: What success have you had with the new direction?

"The success we’ve had with the new direction is we’ve been able to grow our revenue over 90% year over year, and I think we'll be able to continue doing that into 2020 with some of the exciting projects coming up. Growing not just the number of the projects, but the size of those individual projects, too. We've kind of shifted to be more small business than startup ... I think the other thing that we've been able to do really well is kind of expand a little bit outside of the water arena. We do projects now for ... zero-emission battery electric buses, which reduce pollutants in the air that traditional diesel buses emit. We now have kind of this root focus in reducing contaminants in water and now in air. Those are things we worried about being at odds, but those types of projects actually work really well for us."

Q: What are the next steps for your company?

"The direction that we're moving towards is continuing to hopefully grow the team in the next couple of months and amplify our impact that way. Look at metrics not just financially but look at the number of people we've been able to reduce exposure to drinking water contaminants and air pollution. That number just tipped over about 400,000, so that number of people impacted is an important metric for us, too."