For the past several years, building out New Mexico's hydrogen economy has been a focus for many of the state's elected leaders. Although previous pieces of legislation have failed to reach Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham's desk, the state, early last year, launched itself into a joint bid for a large chunk of federal hydrogen-supporting dollars.

Lujan Grisham, along with the governors of Colorado, Utah and Wyoming, signed a memorandum of understanding for a hydrogen funding proposal, dubbed the Western Interstate Hydrogen Hub (WISHH). The states, in combination, picked a group of companies working on hydrogen-related projects that, they feel, are worthy of a federal funding boost.

The 14-month application process culminated in early April this year when the four states submitted their joint application to the U.S. Department of Energy for a $1.25 billion grant. That money, which wouldn't start flowing until next year if awarded, would fuel a group of eight hydrogen production, transportation and usage projects across the four states.

But even though it's a four-state proposal, New Mexico has an outsized position in the joint bid. Of the eight companies included in the final application, four have projects set for the Land of Enchantment; about half of the predicted 26,000 jobs estimated to be created through different hydrogen projects in the proposal could be in New Mexico.

Companies listed in the final WISHH application are:

- AVANGRID

- AVF Energy

- Dominion Energy Utah

- Libertad Power

- Navajo Agricultural Product Industries (NAPI) — Headquartered outside of Farmington, the company declined to provide details to Business First about its involvement in the hydrogen hub proposal and its hydrogen-related work.

- Tallgrass Energy (two projects)

- Xcel Energy Colorado

Those companies included in the proposal agreed to meet environmental standards outlined by the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, for their projects. James Kenney, New Mexico Environmental Department secretary, said the federal government requires those standards to be met in order to invest money.

"There was a lot of back and forth [in] building the architecture of what a solid application looked like and ensuring that the various companies could rise to those occasions," he said. "That took the most time."

Developing New Mexico's hydrogen sector — including through WISHH — has different purposes, according to Kenney. The primary one is to help transition the state to a renewable energy-fueled economy. A potential knock-on effect, he said, is putting pressure on large oil and gas companies with operations in the state to better control their greenhouse gas emissions.

The secretary put it simply.

"We don't get to net zero, we don't reach our ambitious climate goals, we don't decarbonize our economy, we don't hold oil and gas accountable, we don't take the [Bipartisan Infrastructure Law] and [Inflation Reduction Act] funding without hydrogen," he said. "It is a universal connector to the federal dollars, to our climate goals, etcetera."

So, who are the players in New Mexico shaping the state's hydrogen economy? Albuquerque Business First looked at five different companies that are in or adjacent to the hydrogen sector to get a sense of where the industry is at right now — and where it could go from here.

Libertad Power

About a decade ago, a group of energy industry professionals in Santa Fe came together around an opportunity in New Mexico's electricity generation sector — replacing power capacity left as the state's coal plants retire.

Those three professionals — John Campbell, Daniel Klein and Joseph Merlino — formed Libertad Power in 2014. The company, named in the Western Interstate Hydrogen Hub proposal, has plans for hydrogen production plants in the northwest and southeast corners of New Mexico and, down the road, in Arizona, too.

San Juan County, which includes Farmington and Shiprock and stretches to the state's northwest corner, is the firm's initial geographic focus for setting up its hydrogen production, Merlino told Albuquerque Business First. That's where Libertad wants to establish its first production plant.

It already controls a site in the northwest New Mexico county, alongside another in the state's southeastern part. But Merlino said the San Juan hydrogen plant is set to become operational first; Libertad is targeting late 2026 to start producing hydrogen there using electrolysis.

That timeframe is "a little early" in terms of the hydrogen hub timeline, Merlino added — if the Western Interstate Hydrogen Hub application is chosen for federal dollars, money wouldn't start coming through until 2024 and it'd take even longer for projects to get up and running.

"But we think it's very important to sort of get in the market," he said.

Libertad is currently targeting a pair of markets for its hydrogen — transportation, particularly heavy-haul transportation like fuel cell-powered semi-trucks, and energy storage and power generation. But those markets could evolve as new hydrogen usage opportunities emerge, Merlino said.

"One of the things we've learned in looking at this over the years is that it can be very challenging to economically develop a large supply of hydrogen if you're only focused on one set of off-takers or one kind of facility," Merlino said. "It makes it very expensive."

The firm has partnered with Diesel Direct, a large fuel logistics company that would deliver Libertad's hydrogen to users, and Hyundai Motor Co. to engage with prospective off-takes. Being part of the hydrogen hub application means that, if the money is awarded to the four states, Libertad would get a chunk of it for its hydrogen production efforts and future work with those potential hydrogen customers.

"It'll enable us to do things faster and bigger," Merlino said. "To maybe increase the initial production capacity, for example, or increase the ability in a particular mode of hydrogen delivery to customers."

BayoTech

When Albuquerque-based BayoTech Inc. pulled in $157 million in late 2020, it marked the second-largest raise for a New Mexico-based company and shot the hydrogen production and transportation startup's valuation well north of $1 billion. Nearly three years later, the company is close to getting its first hydrogen production facility up and running in a St. Louis exurb with plans for dozens more across the U.S. and, eventually, U.K. and Europe.

That site, which, once operational, could produce around 600 kilograms of hydrogen per day, was built in pieces at Process Equipment and Service Company Inc., or PESCO, in Farmington. Flatbed trucks transported the modules to Wentzville, Missouri, where on-site operators assembled the production facility.

It's a modular model BayoTech, founded in 2015, wants to continue using to build its "hydrogen hubs" in different locations. Those hubs would be small, localized hydrogen production plants that would produce less hydrogen than typical larger facilities but cost less and be quicker to get up and running.

The company plans to use natural gas for its hydrogen production in both renewable and non-renewable forms. Renewable natural gas could come from the byproduct of wastewater treatment plants or landfills, said Catharine Reid, BayoTech's chief marketing officer.

Reid said its Missouri hub will use non-renewable natural gas, but BayoTech's next production facility, currently planned for California, would use a blend of renewable and non-renewable feedstock for hydrogen production. That site, she added, could produce up to 2,000 kilograms of hydrogen per day.

BayoTech has said it can reach a "carbon intensity score" of zero by using just 30% renewable natural gas in its hydrogen production — a measure of how much greenhouse gas is emitted through a production process versus the energy consumed. It has a dozen patents, too, for "bayonet" tubes that hold steam methane reformers that produce hydrogen, a method that captures and reuses heat to save energy.

Emerging hydrogen markets, like transportation in the form of long-haul trucks or bus fleets, are BayoTech's main off-takers for the hydrogen it wants to produce. The company recently partnered with the clean transportation company Nikola Corp., headquartered in Phoenix, for hydrogen transport and offtake in one such deal.

"These fleet operators can access the reliable supply of hydrogen and a local supply," Reid said. "By being local, it really cuts down on costs because we're not paying to transport that hydrogen a great distance."

Although BayoTech's first hub is being set up in Missouri, Reid said the company has a hub site in Albuquerque "under development," which is currently going through the permitting process, she added. The company hopes to have that site operational after its two hubs planned in California come online in 2024.

One challenge for companies like BayoTech, Reid said, is that permitting process.

"There tends to be agreement that there needs to be a focus on clean energy and on transitioning energy, but there's still the red tape and roadblocks when it comes to deploying these projects and getting them through the approval process," she said.

And in terms of the Western Interstate Hydrogen Hub proposal, although not named within the final application, Reid sees an opportunity for BayoTech — especially in its hydrogen transportation business.

"You're never going to have 100% of the hydrogen off-take users directly at the site of production, and there's going to be this need to move hydrogen some distance over the road," she said. "That's one area where BayoTech foresees us being able to participate in these hubs.

"It's helping all across the value chain from the production side through to the demand side," she added about the hubs initiative. "That's great for the industry across the board and for all of the players in New Mexico that are participating."

Tallgrass Energy

In 2020, the Escalante Generating Station, an over 200-megawatt coal-fired power plant in Prewitt, New Mexico, went dark. One year later, a Kansas-based energy company swooped in to snatch up the retired site in a joint deal, with its eyes on converting that existing infrastructure into a hydrogen production plant.

That company is Tallgrass Energy, one of the partners named in the Western Interstate Hydrogen Hub application. It's owned by the New York-based asset managing firm Blackstone, which sealed its over $6 billion deal to purchase the Kansas company's outstanding Class A shares in April 2020.

Tallgrass announced in August 2021 it had purchased a 75% stake in Escalante H2Power, or EH2 Power, the name of the company formed to convert the former coal plant into a hydrogen production facility. Tallgrass bought its majority stake in EH2 Power from Denver-based Brooks Energy Co.; Columbus, Texas-based Newpoint Gas owns the remaining 25% stake in the company, according to reporting by the Kansas City Business Journal at the time of the deal.

Per EH2 Power's website, the company wants to use steam methane reforming to produce hydrogen using natural gas pumped in via existing pipelines. It'd use that hydrogen for electricity generation, to fuel hydrogen-powered transportation and to store. It also plans to sequester carbon emitted from the production process by capturing it and storing it underground.

The Escalante hydrogen plant could produce over 200 megawatts of electricity once in service, which Rachel Carmichael, senior director of communications and public affairs for Tallgrass Energy, told Business First over email could come in 2028. The company expects to start construction in 2026, Carmichael added.

Tallgrass plans to invest over $600 million in the EH2 Power project, according to Carmichael. But, the cost of converting the former coal plant to hydrogen production could be cut down by subsidies included in the Inflation Reduction Act thanks to Tallgrass' plans to sequester the carbon released in production — at a clip of $85 per ton of carbon permanently stored.

That sort of tax break that would make natural gas-powered hydrogen production projects — like Escalante H2Power — more economically viable has drawn scrutiny from environmental analysts, according to a November 2022 New York Times story. The significant energy demands of producing hydrogen via methane reforming and the fallibility of carbon sequestration are two such concerns raised against natural gas-fueled hydrogen production.

"The grid is a tightly integrated system, and we try to be very careful about isolating individual elements without the broader context, especially when discussing decarbonizing the electric system and how tax incentives flow to decarbonized generation," Carmichael wrote in the email to Business First.

Universal Hydrogen

Universal Hydrogen flew onto New Mexico's radar in early 2022 when Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham announced that the Hawthorne, California-based company had plans to stand up an over $250 million manufacturing facility near the Albuquerque International Sunport.

Those plans, which include bringing around 500 employees to New Mexico to staff the manufacturing site, are still in place and still in progress. The state, according to Universal Hydrogen's General Counsel Jon Gordon, would become the company's "manufacturing base" once that site is up and running.

But Gordon added New Mexico presents other opportunities for the California company, too.

"When we shift gears and we think of bringing the network to New Mexico, that's when it really starts to get interesting," he said. "That's where we're looking at off-take from producers, partners for transportation and then also looking to build logistics facilities in underserved communities and hiring people to run them."

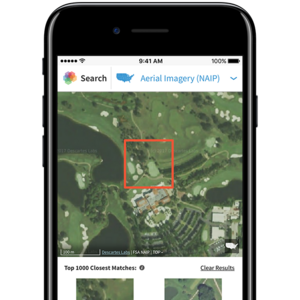

As Gordon alluded to, Universal Hydrogen has some extensive plans for developing a hydrogen transportation network throughout the Land of Enchantment. Essentially, the company wants to set up centralized logistics facilities, called "hydrogen depots" in parts of the state that would receive hydrogen — and hydrogen produced with a zero or very low carbon intensity score, specifically — from producers.

At those depots, the company would fill its hydrogen transport modules and use trucks to move the filled modules to airports. Hydrogen fuel cell-powered aircraft operating at those airports would then take hydrogen out of the modules for their fuel before they are returned to the logistics hubs, inspected and refilled.

And, Universal Hydrogen has some technology to drive that hydrogen transportation network.

For one, it manufactures the modules that would be used to take hydrogen from the hubs to airports. That's the intended purpose of the manufacturing facility the company wants to build in Albuquerque — building those modules at a larger scale.

In addition to the modules, Universal Hydrogen has a hydrogen fuel cell powertrain that can retrofit onto existing regional aircraft. In March, the company flew a testbed aircraft equipped with one of those hydrogen fuel cell powertrains — the first time it had accomplished that feat.

Universal Hydrogen already has some airline partners signed up to purchase those retrofit kits for their aircraft, including upstart Connect Airlines, which has its hub in Toronto and has signed a purchase agreement for 75 kits. Its initial goal is to run regional flights in the Northeast, but John Thomas, the airline's CEO, told Albuquerque Business First the airline could set up routes in the Southwest, including New Mexico.

Those routes include regional flights from Albuquerque to Phoenix, Albuquerque to Denver and Santa Fe to Phoenix, he said.

"We could activate that network with just four aircraft," Thomas said. "It may not sound like much in terms of the four aircraft, but if those four aircraft replace the existing aircraft doing those services, there'd be a savings of just over 70 million pounds of [carbon dioxide] a year.

"We think there is a pretty strong statement there for the state of New Mexico," he continued.

It's thanks to Connect's partnership with Universal Hydrogen that the airline is considering establishing those routes into and out of the Land of Enchantment, Thomas said.

Although hydrogen-powered flights is Universal Hydrogen's focus, Gordon, the company's general counsel, sees it exploring more verticals. Those include different technologies for hydrogen-fueled trucking, ground power units, trains and bus fleets, for example.

"That's the ambition of the company, but I would have to say we haven't made enough progress as I'd like to support these other verticals," Gordon told Business First. "I hope we're able to, now that we've flown, because getting the plane in the air in two years' time — which is unheard of in aviation — we can see ourselves grow to other applications and things that might bring green hydrogen power to communities and places that could use it."

Pajarito Powder

To use hydrogen as a source of fuel, you need what's called a hydrogen fuel cell. Those fuel cells take hydrogen in and use the element to produce electricity. Pajarito Powder, an Albuquerque company in the process of some physical expansion, is working on a suite of products that it thinks can make fuel cells cheaper and more efficient.

Those products are a series of catalysts that are used in both fuel cells and in electrolyzers — a piece of technology required to produce hydrogen with renewable or nuclear electricity. Tom Stephenson, the CEO of Pajarito Powder, said that federally boosted hydrogen production projects could drive demand for both hydrogen generation and hydrogen usage — a potential boon for Pajarito Powder's business.

"Those are the ones that are going to ultimately result in the need for more fuel cells, more electrolyzers and therefore more catalysts to support that," Stephenson said. "That's going to help bring down the economics, which is an essential element of the value proposition."

But it's not just hydrogen hub dollars that could create knock-on demand for Pajarito Powder's catalyst products. The Department of Energy, alongside its hydrogen hub initiative, is also backing research and development into different fuel cell technologies with federal dollars.

That money could bolster Pajarito Powder's own technological scaling, Stephenson said.

The company's currently in the process of setting up shop at a new HQ at 5555 McLeod Road NE in Albuquerque, a move that's been pushed back by supply chain issues. It's also in recent years pulled in investments from some big-name players in the world of hydrogen technology, including Hyundai Motor Co. and Belgium-based Bekaert.

For Stephenson, the state and the country's push toward fueling hydrogen infrastructure signals a meaningful embrace of the fuel source outside of one-off demonstration projects or grant-backed initiatives.

"I'm very bullish, because I think if you look at the level of commitment that the State of New Mexico has made, particularly at the governmental level, to making the transition to hydrogen as a key industry, it's pretty significant," Stephenson said. "I was looking back at a presentation the State did back in January, and we had three cabinet secretaries there participating and driving that and that dialogue, so it's very, very serious."

Hydrogen Vocabulary

Carbon intensity

A measure of how much carbon dioxide is released per unit of electricity produced

Carbon sequestration

The capture, removal and storage of carbon dioxide from the Earth's atmosphere

Electrolysis

The process of using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen

Electrolyzer

A piece of technology required to split hydrogen and oxygen during electrolysis

Fuel cell

An electrochemical cell that creates electricity using the chemical energy of hydrogen, or other fuels, and oxidizing agents

Off-takers

Entities that acquire produced hydrogen for various uses, including transportation and storage, typically negotiated through contracts