In the summer of 2006, NASA launched its New Horizons mission out of Florida's Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 41. Nine years later, a 1,000-pound-plus spacecraft flew past Pluto as part of the mission — the first craft to explore the dwarf planet up close.

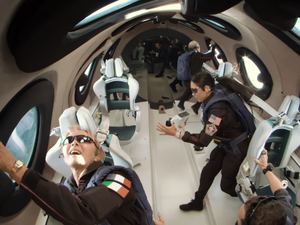

Nearly a decade later still, Alan Stern, Ph.D., a planetary scientist based in Boulder, Colorado — the principal investigator on the New Horizons mission — completed his own space exploration milestone. On Nov. 2, Stern, alongside research Kelli Gerardi, flew into suborbit on board Virgin Galactic's VSS Unity ship.

The mission, dubbed "Galactic 05," marked the second commercial research flight for the Mojave, California-based space travel company this year. Those research missions are a lesser-known but key part of Virgin Galactic's business model going forward, the company's CEO Michael Colglazier has said on recent earnings calls.

But for a company that's marketed itself around, according to U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings, providing "high-net worth individuals with a dynamic spaceflight experience at a fraction of the expense incurred by other private individuals to date," what's the real potential for the research side of Virgin Galactic's business model?

For Stern, who recently sat down with New Mexico Inno for a conversation about his recent Virgin Galactic flight and work as an expert advisor for Santa Fe's Solstar Space Co., that potential is enormous.

Read on for more direct excerpts from New Mexico Inno's conversation with Stern.

This interview was lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

New Mexico Inno: Did the flight meet your expectations? Did the research change at all over the course of the years leading up to the mission?

Alan Stern, Ph.D.: Well that's two different questions, so let me answer the second one first. We contracted for a number of research missions back in 2010 and 2011 — and actually in 2012 as well. And then in 2020, NASA selected my team to be the first to fly on Virgin Galactic, to do a NASA-sponsored research mission. So once that happened, I was no longer just planning to do spaceflight for our own internal company purposes, but for this third-party sponsor.

So we made a change to the first flight to treat it more like a training flight so that on the second flight, which is sponsored by NASA, we'd have a higher probability of success. In other words, like everybody, if you've done something once before you're more likely to succeed the second time than if it's your first time.

So we did change from what was originally going to be a straight-up science experiment to more of a training flight, and that's what we flew [two weeks ago].

It went perfectly. We got what we wanted out of it. We had nine separate objectives, and all nine were completed.

Was it just the time spent in microgravity that you were conducting experiments and the training exercises? Some of the objectives were accomplished other than in microgravity. For example, to become familiar with the sights and the sounds and the accelerations of ascent and reentry. Those were separate objectives so that I would perform better on the NASA-sponsored flight.

What is the timeframe for when you would fly with NASA now that this training is completed? In order for NASA to fund us, two things have to happen. One is already in the past — we have to be selected. Second, Virgin [Galactic] has to satisfy a NASA criteria that they have at least 13 out of 14 flights successful. The catch is Virgin has only flown 10 flights — my flight was the 10th flight. That includes test flights and operational revenue missions. They still have to fly three more flights before NASA will send money to let us contract for that flight.

So it's probably not in the early part of next year, it's probably in the latter part of next year. But that's alright — I waited decades for the first space flight, I can certainly wait one year for the second one.

Bigger picture: I wanted to ask you about Virgin Galactic's goal to continue flying research missions. Are you bullish about the possibility for that to really take off as a part of Virgin's business practice and as a part of the larger commercial aerospace ecosystem? I am. I think it's at least as big a market as the tourist market. Let me justify my answer.

First of all, there are 194 nations on Earth. Only about 40, maybe 40-something, participate in spaceflight. Take the country of Aruba. It's number 130-something on the CIA's list of gross domestic product. It cannot afford orbital spaceflight, interplanetary missions. But for a few hundred thousand dollars, it can afford suborbital spaceflight. So, virtually every nation on Earth can participate in spaceflight activities on vehicles like Virgin [Galactic] and Blue Origin, because their costs are so much dramatically less expensive. It opens up an addressable market.

Moreover, Virgin charges more for a researcher to fly than it does for a tourist to fly, because they have more work to do. They have to not just put a butt in a seat, they have to also make sure that the experiment is safe to fly, and then they have to integrate it into their vehicle and do the training for all that. It's more complicated than training to just be a space tourist.

I don't think we're going to see a lot of people fly suborbital three, four, five, six, seven times. Maybe there's somebody somewhere, but it's not going to be the norm. However, when a researcher flies — let's say you're an astronomer or an oceanography or a microgravity scientist — there's every reason you should be a repeat customer because nobody does one experiment.

We have a much bigger addressable market, we have repeat customers that are uncommon among space tourists, and you can charge more. The bottom line is the researcher market is probably a bigger market in the long run.

Can you clarify for me, then, the relationship between private companies doing suborbital research flights versus what NASA is doing as a government agency? How do you view that relationship? That's complicated, but let me take a minute to explain.

The thing about NASA suborbital is that it's rare, it's expensive and it doesn't involve putting any humans on the flights. Now, contract that to commercial suborbital — it's much more frequent, it's much less expensive and it's about flying people. And as soon as you put people on there, the experiments get less expensive because you don't have to pay for all that automation.

Suppose we built a robot to do what I did on the flight last week. One thing I didn't anticipate is that as the spaceship Unity is maneuvering around and the jets are firing, the walls and the floor of the spacecraft move relative to you when you're floating. That happened, and it surprised me, but all I did was grab something and move over two feet. If we had programmed an experiment to do something, that would have been an unanticipated circumstance and it probably would have failed.

I'm very bullish on the whole thing because as soon as we put people in the loop, we get rid of all that cost of doing things. Think about every other science: Oceanographers go in the ocean on ships, astronomers go to telescopic observatories, volcanologists go to volcanoes, geologists go on expeditions all over the Earth.

Spaceflight has been in this weird cul-de-sac where we had to automate, it was our only option for a long time. And then we figured out, through commercial, how to make it much simpler, much less expensive and much more robust to failure modes by putting people in there. Finally, space scientists, instead of going to a control room at NASA, can go do the experiment the same that geologists do geological expeditions, oceanographers do oceanographic expedition, astronomers go to the telescope — they don't send robots.